Translate this page into:

Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI) as a Predictor Tool for Ovarian Response and Clinical Pregnancy in IVF/ICSI Cycle: A Retrospective Cohort Study

*Corresponding author: Shweta Arora, Department of Infertility and IVF, Akanksha IVF Center and Mata Chanan Devi Hospital, New Delhi, India. drshwetaaroragulati@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Arora S, Nayar KD, Sanan S, Sethi A, Kant G, Sachdeva M, Singh A. Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI) as a Predictor Tool for Ovarian Response and Clinical Pregnancy in IVF/ICSI Cycle: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Fertil Sci Res. 2025;12:4. doi: 10.25259/FSR_26_2024

Abstract

Objectives

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles employ different ovarian stimulation protocols to promote follicle development and boost the number of embryos. Anticipating ovarian response is crucial for maximising treatment effectiveness and minimising complications from under- or over-stimulation. Age, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), and antral follicle count (AFC) are well-known assessors of ovarian response, which makes them established predictors of ovarian response. The Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI) combines these factors to provide a more tailored approach to stimulation protocols, potentially enhancing IVF success rates.

Material and Methods

It was a retrospective cohort study that included 302 patients undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles between March 2021 and March 2023. Patients aged < 39 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 20–30 kg/m², regular menstrual cycles, and no history of ovarian surgery or severe endometriosis were included. AMH levels were measured using chemiluminescent immunoassay, and AFC was assessed by transvaginal ultrasound. ORPI was calculated as (AMH × AFC)/age. Outcomes included total retrieved oocytes, metaphase II (MII) oocytes, and clinical pregnancy rates.

Results

Strong positive correlations were found between ORPI and both total oocytes (r = 0.714, p < 0.0001) and MII oocytes (r = 0.746, p < 0.0001). Univariate logistic regression indicated that age, AMH, AFC, and ORPI were significant predictors of obtaining ≥ 4 oocytes and MII oocytes (p < 0.05). Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis demonstrated that ORPI has excellent discriminative ability for predicting ≥4 oocytes (AUC = 0.907), ≥4 MII oocytes (AUC = 0.937), and clinical pregnancy (AUC = 0.822), with optimal cutoff values established.

Conclusion

ORPI, which combines age, AMH, and AFC, strongly predicts ovarian response and clinical pregnancy in IVF/ICSI cycles. It can help formulate personalised ovarian stimulation protocols, potentially enhancing patient counselling and treatment outcomes.

Keywords

AFC

AMH

Clinical pregnancy

ICSI

Infertility

IVF

Ovarian response

INTRODUCTION

In in vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles, different ovulation induction protocols are utilised to stimulate the development of multiple follicles, thereby increasing the number of embryos available for selection and transfer.[1] Predicting hypo-response or hyper-response can be a daunting task. Increased oestrogen levels, arising from the development of multiple follicles, can have an adverse impact on both embryo quality and the endometrium.[2] However, understanding a patient’s potential ovarian response allows for the adjustment of gonadotropin dosages, which helps prevent the negative effects of excessive ovarian stimulation and decreases the chances of cycle cancellations. This personalised approach enhances the success and cost-effectiveness of ovarian stimulation regimens. Various factors can predict ovarian response, including age, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count (AFC), ovarian volume, day 2 follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), oestradiol, inhibin, and dynamic tests. Among these, age, AFC, and AMH have demonstrated the highest reliability and effectiveness.[3]

The initial factor considered when assessing ovarian reserve is the patient’s age. Although both the quantity and quality of eggs decrease with age, there is significant variation across different races, leading to varying responses to ovarian stimulation.[4] Rather than chronological age, biological age, which is predicted by hormonal and functional profiles, is a better factor to take into consideration.[5] The AFC, a measurement of follicles sized between 2 and 9 mm in both ovaries on days 2 or 3 of the menstrual cycle using transvaginal ultrasound (TVS), is also used for predicting the ovarian response. However, subjective variations and cycle-to-cycle variability limit its use.[6] AMH is a member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily and is secreted by granulosa cells of pre-antral and small antral follicles.[7] AMH serves as a direct marker for ovarian reserve and functions independently of FSH. Unlike FSH, AMH levels remain consistent throughout the menstrual cycle and gradually decline over a woman’s reproductive years, eventually becoming undetectable after menopause.[8] Therefore, all these markers have inherent inaccuracies and are generally unreliable for predicting the number or quality of remaining oocytes in the ovaries or the likelihood of pregnancy after infertility treatment.[9]

Considering benefits like ability to correctly determine the gonadotropin dose, reducing complications and failure rates, and improving the cost-benefit ratio of ovarian stimulation protocols, our study is using the Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI), which is based on all 3 markers, viz., age, AMH, and AFC,[10] to assess the ovarian response to stimulation in IVF/ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) cycles by correlating it with the number of oocytes retrieved, the number of mature metaphase II (MII) oocytes retrieved, and the clinical pregnancy rate.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

It is a retrospective cohort study involving 302 patients undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles over a period from March 2021 to March 2023 at our infertility clinic. The study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee, and clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board.

All patients included in the study were less than 39 years of age and had a BMI between 20 and 30 kg/m². They also had regular menstrual cycles, both ovaries were present, there was no history of ovarian surgery or severe endometriosis, and there was no evidence of endocrine disorders. The only exclusion criterion was the presence of ovarian cysts identified by TVS.

AMH measurement

A venous blood sample was taken before the scheduled treatment (minimum 30 days) during the early follicular menstrual cycle phase. It was measured using the Access AMH assay—chemiluminescent immunoassay. This assay has a minimum detection limit of 0.01 ng/ml, with intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation not exceeding 3.3% and 6.5%, respectively.

AFC

TVS was performed during the early follicular phase, and all ovarian follicles measuring 2–10 mm were counted, with the total for both ovaries referred to as the basal AFC. The AFC has a strong correlation with chronological age in normally fertile women and appears to reflect the remaining pool of primordial follicles.[11]

ORPI calculation

The ORPI values were calculated by multiplying the AMH (ng/ml) level by the number of antral follicles (2–10 mm), and the result was divided by the age (years): ORPI = (AMH × AFC)/ patient age.[10] This equation is built upon earlier findings indicating that ovarian response to stimulation is directly proportional to AMH levels and the number of antral follicles and inversely proportional to the patient’s age.

End points

The primary outcomes measured were the total number of retrieved oocytes and the count of MII oocytes. The secondary outcome was clinical pregnancy (a pregnancy diagnosed by ultrasonographic visualisation of at least one gestational sac with or without cardiac activity inside the uterine cavity).

Statistical analysis

The presentation of the categorical variables was done in the form of numbers and percentages (%). On the other hand, the quantitative data were presented as the means ± SD and as the median with 25th and 75th percentiles (interquartile range). The following statistical tests were applied to the results:

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for the correlation of ORPI with the number of oocytes and the number of MII oocytes.

Univariate logistic regression was used to find out significant factors of the number of oocytes ≥4, the number of MII oocytes ≥4, and positive clinical pregnancy.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to access the cutoff point, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of ORPI for predicting the number of oocytes ≥4, the number of MII oocytes ≥4, and positive clinical pregnancy. The discriminative performance of the model was assessed by the area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve.

The data entry was done in the Microsoft EXCEL spreadsheet, and the final analysis was done with the use of Statistical Package for Social Sciences software, IBM manufacturer, Chicago, USA, ver. 25.0.

For statistical significance, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The general characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1. Of all 302 female patients that were enrolled in the study, the mean age was 31.75 ± 4 years (range 20–44), the mean AMH level was 3.75 ± 3.39 ng/ml (range 0.05–18.6), and the mean AFC was 7.1 ± 2.94 (range 0–14). The mean ORPI was 1.06 ± 1.22 (range 0–6.76). In 281 cases (93.05%), the number of oocytes was ≥4, while in 21 cases (6.95%), it was <4. The mean number of oocytes for study subjects was 11.17 ± 5.62 (range 1–30). For MII oocytes, 240 cases (79.47%) had 4 or more, and 62 cases (20.53%) had <4. The mean number of MII oocytes for study subjects was 7.15 ± 3.83 (range 0–18). For clinical pregnancy, 197 cases (65.23%) were positive, and 105 cases (34.77%) were negative.

| Parameters | n (%) | Mean ± SD | Median (25th–75th percentile) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of oocytes | ||||

| <4 | 21 (6.95%) | 11.17 ± 5.62 | 10 (7–15.75) | 1–30 |

| ≥4 | 281 (93.05%) | |||

| Number of MII oocytes | ||||

| <4 | 62 (20.53%) | 7.15 ± 3.83 | 7 (4–10) | 0–18 |

| ≥4 | 240 (79.47%) | |||

| Clinical pregnancy | ||||

| No | 105 (34.77%) | – | – | – |

| Yes | 197 (65.23%) | |||

| Age (years) | – | 31.75 ± 4 | 32 (29–34) | 20–44 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | – | 3.75 ± 3.39 | 2.65 (1.402–4.91) | 0.05–18.6 |

| ORPI | – | 1.06 ± 1.22 | 0.64 (0.203–1.398) | 0–6.76 |

| AFC | – | 7.1 ± 2.94 | 7 (5–9) | 0–14 |

SD: Standard deviation, MII: Metaphase II, AMH: Anti-Müllerian hormone, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, AFC: Antral follicle count.

The Spearman rank correlation analysis demonstrated significant (p < 0.05) positive correlations between the ORPI and the total number of oocytes collected and the total number of MII oocytes collected, with correlation coefficients of 0.714 and 0.746, respectively [Table 2].

| Variables | Number of oocytes | Number of MII oocytes |

|---|---|---|

| ORPI | ||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.714 | 0.746 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, MII: Metaphase II.

Spearman rank correlation coefficient

On performing univariate regression, age (years), AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI were significant factors affecting the number of oocytes ≥4. With the increase in age (years), the chances of the number of oocytes ≥4 significantly decrease with an odds ratio of 0.824 (0.733–0.926). With the increase in AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI, the chances of having a number of oocytes ≥4 significantly increase with odds ratios of 3.114 (1.762–5.502), 2.38 (1.738–3.26), and 42.12 (15.04–117.80), respectively [Table 3].

| Variable | Beta coefficient | Standard error | p-value | Odds ratio | OR lower bound (95%) | OR upper bound (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.193 | 0.060 | 0.001 | 0.824 | 0.733 | 0.926 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 1.136 | 0.290 | <0.0001 | 3.114 | 1.762 | 5.502 |

| AFC | 0.867 | 0.161 | <0.0001 | 2.380 | 1.738 | 3.260 |

| ORPI | 3.74 | 0.525 | 0.0002 | 42.12 | 15.04 | 117.80 |

AMH: Anti-Müllerian hormone, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, AFC: Antral follicle count, OR: Odds ratio.

On performing univariate regression, age (years), AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI were significant factors affecting the number of MII oocytes ≥4. With the increase in age (years), the chances of the number of MII oocytes ≥4 significantly decrease with an odds ratio of 0.861 (0.798–0.929). With the increase in AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI, the chance of the number of MII oocytes ≥4 significantly increases with odds ratios of 3.305 (2.276–4.799), 4.655 (3.018–7.179), and 12.63 (8.754–18.22), respectively [Table 4].

| Variable | Beta coefficient | Standard error | p-value | Odds ratio | OR lower bound (95%) | OR upper bound (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.149 | 0.039 | 0.0001 | 0.861 | 0.798 | 0.929 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 1.195 | 0.190 | <0.0001 | 3.305 | 2.276 | 4.799 |

| AFC | 1.538 | 0.221 | <0.0001 | 4.655 | 3.018 | 7.179 |

| ORPI | 2.536 | 0.187 | <0.0001 | 12.63 | 8.754 | 18.22 |

AMH: Anti-Müllerian hormone, MII: Metaphase II, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, AFC: Antral follicle count, OR: Odds ratio.

On performing univariate regression, age (years), AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI were significant factors of positive clinical pregnancy. With the increase in age (years), the chance of positive clinical pregnancy significantly decreases with an odds ratio of 0.9 (0.818–0.992). With the increase in AMH (ng/ml), AFC, and ORPI, the chance of positive clinical pregnancy significantly increases with odds ratios of 1.493 (1.251–1.781), 1.491 (1.272–1.748), and 3.525 (2.084–5.964), respectively [Table 5].

| Variable | Beta coefficient | Standard error | p-value | Odds ratio | OR lower bound (95%) | OR upper bound (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.105 | 0.049 | 0.033 | 0.900 | 0.818 | 0.992 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 0.401 | 0.090 | <0.0001 | 1.493 | 1.251 | 1.781 |

| AFC | 0.400 | 0.081 | <0.0001 | 1.491 | 1.272 | 1.748 |

| ORPI | 1.260 | 0.268 | <0.0001 | 3.525 | 2.084 | 5.964 |

AMH: Anti-Müllerian hormone, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, AFC: Antral follicle count, OR: Odds ratio.

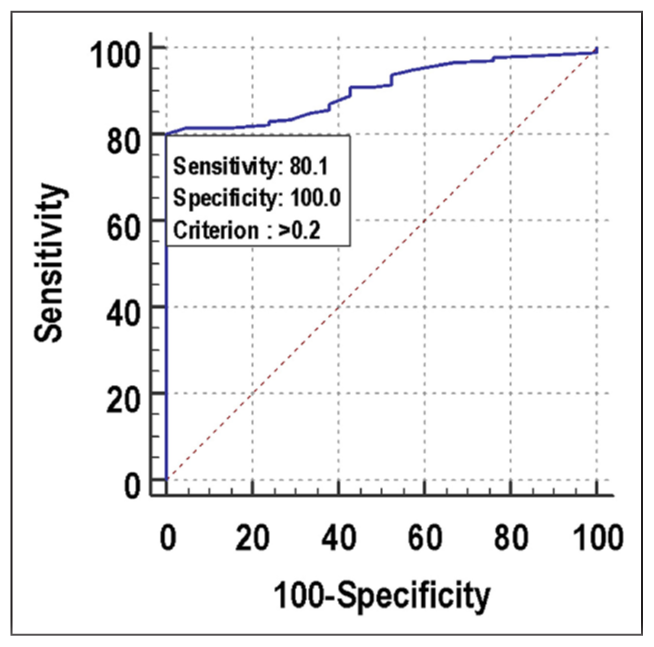

The performance of the ORPI as a prognostic test was observed using ROC curves. Regarding the probability of collecting a number of oocytes ≥4, the ROC curve showed that the performance of ORPI (AUC 0.907; 95% CI: 0.868–0.937) was outstanding. ORPI was the significant predictor of the number of oocytes ≥4 at an ff point of >0.2 with an AUC of 0.907 for correctly predicting the number of oocytes ≥4. It also showed that of the patients who had the number of oocytes ≥4, 80.07% of patients had ORPI >0.2. If ORPI > 0.2, then there was a 100.00% probability of the number of oocytes ≥4, and if ORPI ≤ 0.2, then there was a 27.30% chance of the number of oocytes <4. Among patients who had the number of oocytes <4, 100.00% of patients had ORPI ≤0.2 [Figure 1, Table 6].

- ROC curve for ORPI for predicting number of oocytes ≥4. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Area under the ROC curve | 0.907 |

| Standard error | 0.0199 |

| 95% confidence interval | 0.868–0.937 |

| p-value | <0.0001 |

| Cutoff | >0.2 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 80.07% (74.9%–84.6%) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 100% (83.9%–100.0%) |

| PPV (95% CI) | 100% (98.4%–100.0%) |

| NPV (95% CI) | 27.3% (17.7%–38.6%) |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 82.12% |

ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, CI: Confidence interval, PPV: Positive predictive value, NPV: Negative predictive value.

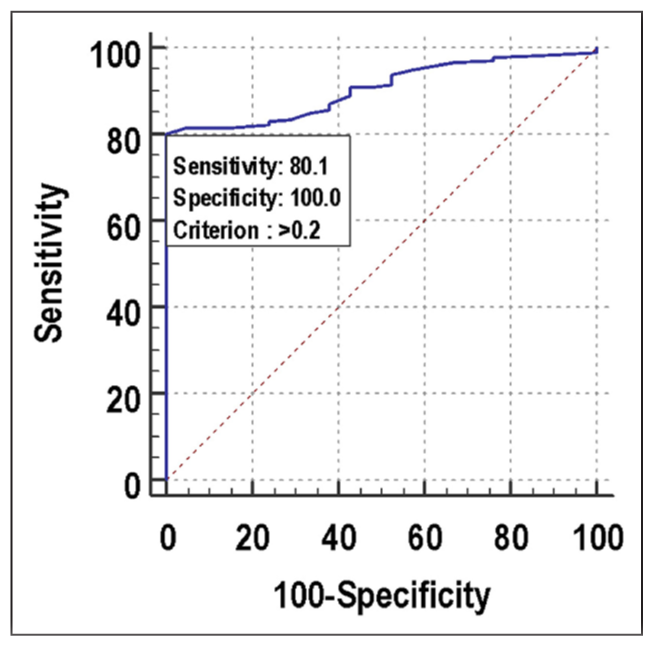

Regarding the probability of collecting several MII oocytes ≥4, the ROC curve showed that the performance of ORPI (AUC 0.937; 95% CI: 0.903–0.962) was outstanding. ORPI was the significant predictor of the number of MII oocytes ≥4 at a cutoff point of >0.2 with an AUC of 0.937 for correctly predicting the number of MII oocytes ≥4. It also showed that of the patients who had the number of MII oocytes ≥4, 90.42% of patients had ORPI > 0.2. If ORPI > 0.2, then there was a 96.40% probability of the number of MII oocytes ≥4, and if ORPI ≤ 0.2, then 70.10% chance of the number of MII oocytes <4. Among patients who had the number of MII oocytes <4, 87.10% of patients had ORPI ≤ 0.2 [Figure 2, Table 7].

- ROC curve for ORPI for predicting number of MII oocytes ≥4. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, MII: Metaphase II.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Area under the ROC curve | 0.937 |

| Standard error | 0.0168 |

| 95% confidence interval | 0.903–0.962 |

| p-value | <0.0001 |

| Cutoff | >0.2 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 90.42% (86.0%–93.8%) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 87.1% (76.1%–94.3%) |

| PPV (95% CI) | 96.4% (93.1%–98.5%) |

| NPV (95% CI) | 70.1% (58.6%–80.0%) |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 89.74% |

ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, MII: Metaphase II, CI: Confidence interval, PPV: Positive predictive value, NPV: Negative predictive value

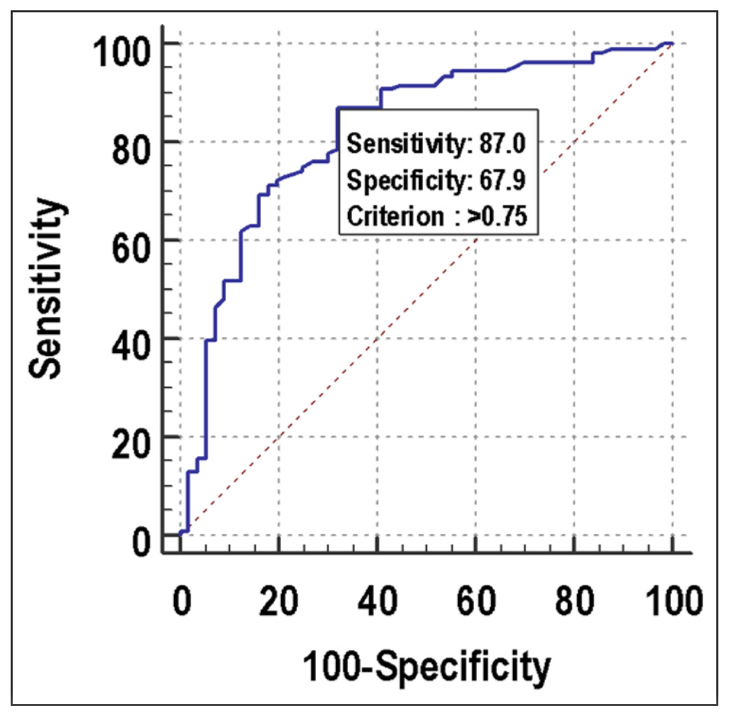

As far as predicting the probability of clinical pregnancy, the discriminatory power of ORPI (AUC 0.822; 95% CI: 0.754–0.877) was excellent. ORPI was the significant predictor of positive clinical pregnancy at a cutoff point of >0.75 with an AUC of 0.822 for correctly predicting positive clinical pregnancy. It also showed that of the patients who had positive clinical pregnancy, 87.04% of patients had ORPI >0.75. If ORPI > 0.75, then there was an 83.90% probability of positive clinical pregnancy, and if ORPI ≤ 0.75, then there was a 73.10% chance of negative clinical pregnancy. Among patients who had negative clinical pregnancy, 67.86% of patients had ORPI ≤ 0.75 [Figure 3, Table 8].

- ROC curve for ORPI for predicting clinical pregnancy. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Area under the ROC curve | 0.822 |

| Standard error | 0.0361 |

| 95% confidence interval | 0.754–0.877 |

| p-value | <0.0001 |

| Cutoff | >0.75 |

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | 87.04% (79.2%–92.7%) |

| Specificity (95% CI) | 67.86% (54.0%–79.7%) |

| PPV (95% CI) | 83.9% (75.8%–90.2%) |

| NPV (95% CI) | 73.1% (59.0%–84.4%) |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 79.88% |

ROC: Receiver operating characteristic, ORPI: Ovarian response prediction index, CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Despite advancements in reproductive medicine, poor ovarian response and excessive ovarian response during controlled ovarian stimulation still pose major challenges for many programs. A reliable indicator for accurately predicting patients’ ovarian response could significantly enhance the customisation and optimisation of controlled ovarian stimulation protocols before treatment cycles start. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Consensus Conference has established a standardised definition for poor ovarian response, which is defined as retrieving fewer than 4 oocytes in a standard IVF protocol.[12] A “high response” is generally defined as retrieving more than 15 oocytes following a standard controlled ovarian stimulation protocol.[13] Predicting both high and poor responses is imperative for the management and proper counselling of patients.

Depending only on age to predict ovarian response to gonadotropin stimulation may not always be sufficient, given the considerable variability in ovarian response even among women of the same age group.[14] Variations among individuals are influenced by genetic and environmental factors that determine the initial size of the primordial follicle pool at birth and affect the rate at which this pool diminishes during reproductive life.[15] Basal FSH, which is widely utilised at many centres, has demonstrated superior effectiveness as a marker of individual ovarian reserve compared to age.[16] However, its ability to predict poor response is only moderate, necessitating very high basal FSH levels to accurately predict absolute poor response.[17] Several studies have highlighted AFC as a useful marker to predict ovarian reserve.[18,19] But its dependence on a high-resolution ultrasound machine and huge inter and intra-observer variation limits its usage. AMH is gonadotropin independent and thus, its value remains consistent throughout the menstrual cycle.[20] However AMH measurements vary due to the use of different commercially available assays and their respective cutoff values. Furthermore, inadequate storage and mishandling of samples may result in a substantial elevation of AMH levels.[21] Polycystic Ovarian Disease, contraceptive use, and vitamin D levels also influence AMH levels.[22,23]

Thus, based on current literature, no single test of ovarian reserve can reliably predict ovarian response in IVF cycles. ORPI, which is an integration of various variables, is a more accurate index for predicting ovarian response. The results of our study show that ORPI has a statistically significant correlation with the number of oocytes and mature/MII oocytes retrieved. Another study by Haritha et al. reported similar results.[24] Our study shows that ORPI is far superior to AFC, AMH, and age to predict an adequate number of oocytes, MII oocytes, and incidence of clinical pregnancy after the IVF/ICSI cycle. Oehninger et al. in 2015 showed that ORPI and AFC both have similar predictive values for the prediction of ovarian response.[25] Nelson et al. (2015) found a better predictive value of AMH versus AFC for oocyte yield.[26] In their study, Freiesleben and colleagues determined that the optimal prognostic model for predicting a low response incorporated AFC and age, suggesting further enhancement through the integration of serum AMH levels into the ORPI calculation.[27] Some studies indicate AFC as a superior marker compared to AMH,[28,29] whereas others suggest AMH is more reliable.[30,31] Our study, however, did not find a significant difference between AFC and AMH in predicting ovarian response. The ROC curve also demonstrates that ORPI has very high specificity and sensitivity to predict the outcomes. Therefore, since there is no universally applicable ovarian stimulation regimen for all patients. Given its predictive potential, ORPI could be employed to customise medication doses and/or ovarian stimulation regimens based on individual needs.

However, despite enrolling all eligible patients during the study period, the sample size is limited. Additionally, our study did not measure the live birth rate, which is another important outcome. Furthermore, we did not compare our findings with other clinical, endocrine, ultrasound markers, or dynamic tests. Therefore, more well-designed studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to explore the potential role of ORPI in clinical practice, particularly for counselling and selecting individualised stimulation protocols.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that ORPI, a novel ovarian response biomarker comprising a straightforward index of 3 variables, has remarkable efficacy in predicting ovarian response and clinical pregnancy. This tool holds promise in tailoring personalised controlled ovarian stimulation programs, thus aiding in counselling and prognostication for couples facing infertility.

Author contribution

KDN, SS, AS: Conceptualisation; MS: Data collection; GK, AS: Execution.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board with approval number MCDH/2023/28, dated 25-09-2023.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent is not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

- Is Ovarian Stimulation Detrimental to the Endometrium? Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15:45-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of Ovarian Response: Progress Towards Individualized Treatment in Ovulation Induction and Ovarian Stimulation. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Systematic Review of Tests Predicting Ovarian Reserve and IVF Outcome. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:685-718.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hormonal, Functional and Genetic Biomarkers in Controlled Ovarian Stimulation: Tools for Matching Patients and Protocols. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.. 2012;10:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Antral Follicle Count Predicts the Outcome of Pregnancy in a Controlled Ovarian Hyperstimulation/Intrauterine Insemination Program. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:12-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- TGF-Beta Superfamily Members and Ovarian Follicle Development. Reproduction. 2006;132((2)):191-206.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Applications of Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Measurements in Both Males and Females: An Update.Innovation (Camb) . 2021;2((1)):100091.

- [Google Scholar]

- A simple Multivariate Score Could Predict Ovarian Reserve, as Well as Pregnancy Rate, in Infertile Women. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:655-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- A New Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI): Implications for Individualised Controlled Ovarian Stimulation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.. 2012;10:94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antral Follicle Count in Normal (Fertility-Proven) and Infertile Indian Women. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2014;24((3)):297-302.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESHRE Consensus on the Definition of ‘Poor Response’ to Ovarian Stimulation for in Vitro Fertilization: The Bologna Criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1616-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti- Müllerian Hormone (AMH) as a Predictive Marker in Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16((2)):113-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antral Follicle Count, Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Inhibin B: Predictors of Ovarian Response in Assisted Reproductive Technology? BJOG. 2005;112:1384-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of Ovarian Reserve—Should we Perform Tests of Ovarian Reserve Routinely? Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2729-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age and Basal FSH as a Predictor of ART Outcome. Iranian J Reproduct Med. 2009;7((1)):19-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-Specific Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels in Women With and Without Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2014;102((1)):230-6.e2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian Volume and Antral Follicle Count for the Prediction of Low and Hyper Responders With in Vitro Fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.. 2007;5:9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Cohort of Antral Follicles Measuring 2–6 mm Reflects the Quantitative Status of Ovarian Reserve as Assessed by Serum Levels of Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Response to Controlled Ovarian Stimulation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94((5)):1775-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biomarkers of Ovarian Response: Current and Future Applications. Fertil Steril. 2013;99((4)):963-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Müllerian Hormone as Predictoro of Implantation and Clinical Pregnancy After Assisted Conception: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;103((1)):119-30.e3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Long-Term Using of Hormonal Contraception on Anti-Müllerian Hormone Secretion. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32((5)):383.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Effect of Vitamin D Status on Ovarian Reserve Markers in Infertile Women: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd). 2020;18((2)):85-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of Ovarian Response With Ovarian Response Prediction Index (ORPI) During Controlled Ovarian Stimulation in IVF. J Infertil Reprod Biol. 2020;8((3)):33-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive Factors for Ovarian Response in a Corifollitropin alfa/GnRH Antagonist Protocol for Controlled Ovarian Stimulation in IVF/ICSI Cycles. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.. 2015;13:117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Anti-Müllerian Hormone Levels and Antral Follicle Count as Predictor of Ovarian Response to Controlled Ovarian Stimulation in Good-Prognosis Patients at Individual Fertility Clinics in Two Multicenter Trials. Fertil Steril. 2015;103((4)):923-30.e1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk Charts to Identify Low and Excessive Responders Among First-Cycle IVF/ICSI standard Patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:50-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Müllerian Hormone and Antral Follicle Count as Predictors of Ovarian Response in Assisted Reproduction. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2013;6((1)):27-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antral Follicle Count Determines Poor Ovarian Response Better Than Anti-Müllerian Hormone But Age is the Only Predictor for Live Birth in Vitro Fertilization Cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30((5)):657-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Müllerian Hormone as a Predictor of IVF Outcome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14((5)):602-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Müllerian Hormone: Correlation of Early Follicular, Ovulatory and Midluteal Levels With Ovarian Response and Cycle Outcome In Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Patients. Fertil Steril. 2008;89((6)):1670-6.

- [Google Scholar]