Translate this page into:

Pains of the bane of infertile women in Southwest Nigeria: a qualitative approach

Address for correspondence: Dr. Lateef Olutoyin Oluwole, MBBS, FWACP, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. E-mail: sartolu1@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Infertility can be painful as it affects every aspect of life and relationship. In traditional African societies children are of great socioeconomic value. The invisible grieving of women living with infertility is enormous, and exposes such women to sundry psychological burden.

Aims:

This study qualitatively explored the viewpoints, and the psychological burden of women living with infertility in southwest Nigeria.

Settings and Design:

This study adopted a qualitative approach to investigate the experience of women who were undergoing treatment for infertility at a tertiary health facility in southwest Nigeria.

Methods and Material:

A qualitative approach was adopted for profound exploration with a view to appraising their holistic subjective experiences of infertility.

Statistical analysis:

Data for analysis was obtained through verbatim transcription of interview as recorded by audio recorder and note taking. Systematic text condensation was used to analyze the data.

Results:

Majority of the participants who were in monogamous relationship were religious and lived with their spouses. A total of 43 significant statements were discerned and sorted into 8 themes including isolation, anxiety, shame, low self-esteem, anger cum resentment, and hopelessness.

Conclusions:

It would require a multi-disciplinary approach to relieve the pains, and alleviate the baneful experience of infertile couples.

Keywords

Infertility

Nigeria

pains

southwest

Key Messages: The psychological distress of infertile women is a reality with associated psychosocial stressors. These psychological problems are, however, not insurmountable. It is worthwhile to engage mental health practitioners in the holistic care of couple living with infertility.

INTRODUCTION

The Holy Bible recorded in Genesis 30 verse 1 that Rachael cried to her husband: “give me a child or I die”. This record illustrates that since ancient times a high premium is placed on having children. In essence, children are regarded as one’s identity, and in fact, are the vehicles of self perpetuation.[1] This is particularly relevant in African society where children are regarded as a way of dealing with mortality, and highly valued for socioeconomic reasons.[2,3] The Yoruba tribe of southwest Nigeria views children as “ade ori” meaning crown worn on the head.

An epidemiological definition of infertility has been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the inability to conceive within two years of exposure to pregnancy.[4] Infertility is a growing issue of major public health concern and affects an estimated 10%–15% of couples of reproductive age.[5,6] Worldwide, more than 70 million couples suffer from infertility, the majority being residents of developing countries.[7] The prevalence of infertility in sub-Saharan African varies widely from 9% in the Gambia, 21.2% in Northwestern Ethiopia to 30% in Nigeria.[8,9,10]

In traditional African societies where infertility is mainly regarded as a curse, infertility often results in significant distress that may affect the overall existence of a couple, with the woman carrying the largest burden of suffering.[11,12] Earlier study from the region where this present study was done among the Ekiti of southwest Nigeria reported women were treated as outcast, after they die, and their bodies are buried on the outskirt of the town with those of the people experiencing mental illness.[13] Outside African culture, in the Middle East, women’s social status, dignity and self-esteem depend on her ability to procreate.[14]

Due to grieving which remains invisible for most parts, inability to achieve pregnancy is usually coupled with low self-confidence, depression, sexual problems, feeling of shame or guilt and lack of communication with friends and family members.[15] Studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have established the occurrence of psychological stressors as common consequence of infertility.[16,17] The associated psychological distress often experienced by infertile women or couples is due to inability to achieve the desired social role.[18] Reproductive failure has very far reaching social implication in Nigeria where, traditionally, the main reason for marriage is to have children irrespective of whether or not the couple is in love.[19]

This study explored the viewpoints, and the psychological burden of infertility that exposes the bane and pains of infertile women, with a view to understanding their concerns. Literature suggests that infertility is more stressful for women than for men and most of therapeutic procedures are performed on females thus causing more anxiety and depression in women.[20,21] This study adopted a qualitative approach to investigate the experience of women who were undergoing treatment for infertility at a tertiary health facility in southwest Nigeria.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A qualitative approach was adopted for profound exploration with a view to appraising their holistic subjective experiences of infertility. This methodological framework provides tools for profound exploration of human experiences so as to enable appraisal of actual and totality of experiences of the participants. The participants in the study were recruited through purposive sampling method that enabled maximum variation as it regarded the varying types, causes, treatment and, duration of infertility as experienced by the participants. The inclusion criteria for the study were (i) participants have been mentally stable for two years or more, (ii) psychosexual history revealed inability to conceive at least one year after marriage, (iii) diagnosis of infertility by specialist(s); (iv) participants consented to interview process. Exclusion criteria included individuals who refused to give verbal or written consent.

Recruited participants were interacted with in Yoruba language (the native and predominant language in the area of study) except for five of the participants who were interviewed in English language because they were not fluent in Yoruba language. The eventual translation and back translation of the responses in Yoruba language into English language was done by the first author who is proficient in both languages.

An interview proforma was filled by the interviewer to capture the sociodemographic and sexual history of each of the participants. An in-depth, face-to face, interview was adopted with a sound recorder and back-up notes. The participants were encouraged to be relaxed while they relate their experiences concerning infertility. A close observation of body language was made to detect any emotional distress in some of the participants as they recounted their infertility experiences. Such reactions were promptly addressed by the first author through counselling. The focus of the study exploration was: “Do tell me your experiences with infertility”. Further explorative questions were asked to clarify and guide the focus of the interview.

Ethical approval for the study was sought and obtained from the ethics committee of the authors’ tertiary institution. Informed consents were given by the participants after the authors had explained the entire process of the interview concerning this study. The participants were also made to understand that their confidentiality and rights to decline participation at any stage of the interaction were guaranteed. All documentations related to the study were carefully handled.

Data analysis

Data for analysis were obtained through verbatim transcription of interview as recorded by audio recorder and note taking. Systematic text condensation was used to analyze the data.[22] This process involved transcription, sorting out themes from the total impression of the transcribed details, identifying formulated meanings from the themes; meanings were then condensed and synthesized to descriptions and concepts.

Forty-three significant statements were extracted and were clustered into eight themes after extensive and exhaustive description of the participants’ recount of their experiences of infertility. The data were analysed concurrently following agreement by the authors on the sorted themes and meanings.

RESULTS

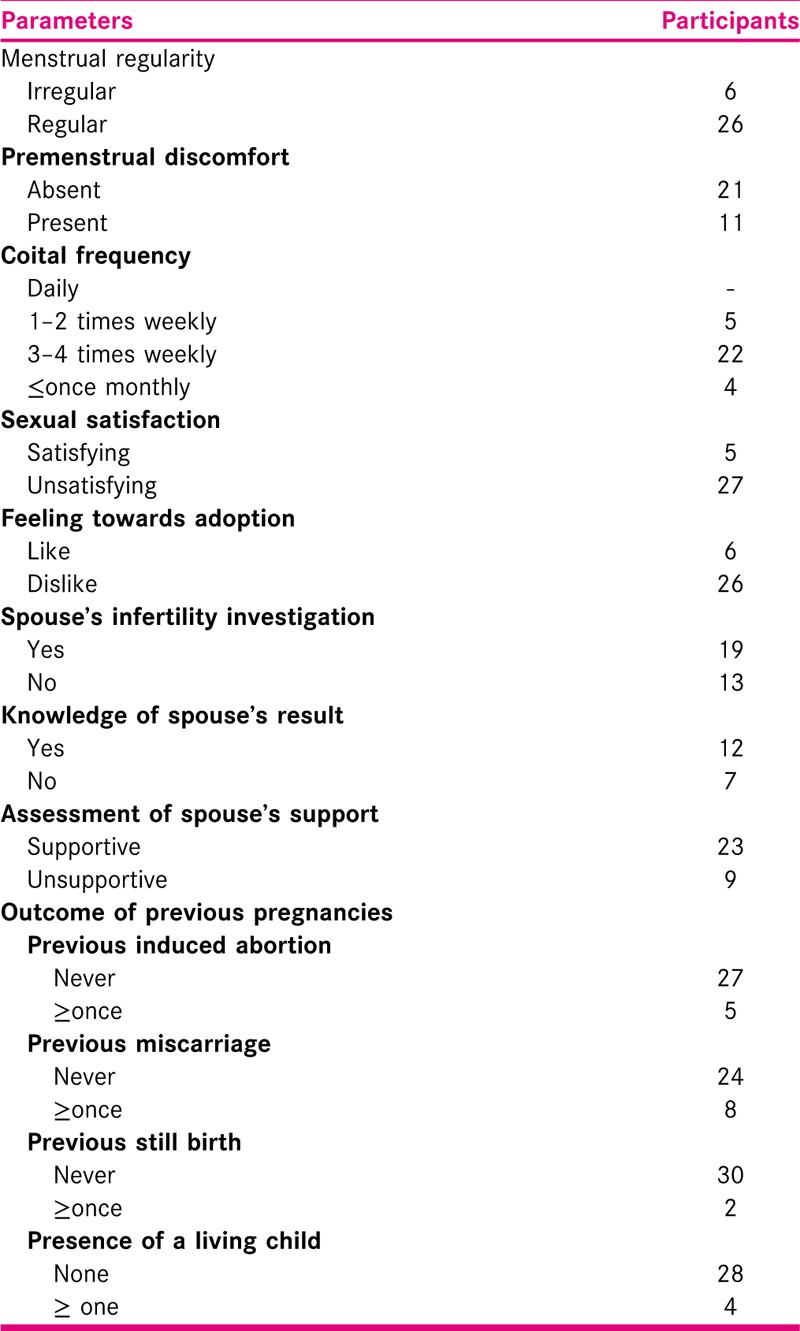

The study started with thirty-nine participants who gave consent but four later declined and another three participants had to be excluded due to profound emotional reactions that would not allow them to complete the interview session. The study was completed with only thirty-two women living with infertility. The sociodemographic variables of the participants are shown in Table 1 and Table 2 shows some aspects of the gynaecological history of the participants.

The mean age of participants was 34.0 ± 5.52 years and age ranged between 28 to 47 years. Thirteen (41%) of the participants had primary infertility and nineteen (59%) had secondary infertility. Mean duration of infertility was 4.19 ± 2.25 with a range of between 1 to 17 years, and their treatment ranged between 4 months to 14 years. Only four (21%) of the 19 participants with secondary infertility had a living child each.

In spite of the majority of the participants admitting coital frequency between three and four times weekly, 27(84%) of the participants considered their sexual experience with spouse unsatisfying. Four-fifth of the women in this study expressed their dislike for adoption. About a third of the participants were not aware of the outcome of the results of infertility investigations of their spouses. However, about three-quarter of the participants admitted spouse were supportive. Only seven of the thirty-two participants had their spouses accompanied them, at least once, to the clinic while duration of this study.

Emerging themes

A total of 43 significant statements were noted and were sorted into eight main themes. Discerned themes and examples of related statements by the participants are shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Similar to findings in some earlier studies which had observed overwhelming negative experiences, this study revealed, among others challenges, problems of isolation, anxiety, shame, low self-esteem, anger cum resentment, and hopelessness. Negative consequences of infertility are common in developing countries.[23]

Isolation

In addition to infertility being a medical condition, it causes serious emotional problems in individuals and marital relations.[24] Relational problem may occur, on one hand, between couple living with infertility, and also with family and friends. More often than not, woman having the challenge of infertility may be stigmatized; and the husband may abandon her in efforts to de-stigmatize himself. One of the participants detailed how her in-laws have abandoned her family. This, she claimed caused her husband to neglect her. My husband is threatening a divorce, she lamented. This may happen truly because of the tendency of the society to blame the woman for infertility. My in-laws are not visiting us anymore. They have stopped inviting my husband for discussions on family issues, a participant reported. An earlier study had observed infertile women are likely to experience mental and emotional abuse or divorce from their partners and their in-laws.[25] It is important, however, that majority of the participants in this study had their spouse’ support in their plight.

Anxiety

A woman having problem of infertility could live anxious over a period from time of diagnosis to the worrying times of treatment when realities are falling short of expectations regarding treatment outcomes. One of the participants tried to depict her experience of moments she had to receive result of pregnancy test during treatment: I often would ask my husband to collect the result from the laboratory because I’m afraid. I remember on occasions I was afraid while my husband handed results to me, and shaking his head pitifully. The result was negative.

Shame

The reality of infertile women not fulfilling personal desires; meeting family expectation cum cultural roles to become parents may lead to shame. Disappointment sometimes expressed by families of infertile woman may amplify the guilt and shame felt by the infertile individual.[26] Also, the intrusive nature of treatment for infertility may cause experience of shame. More than half of the participants admitted to experience of shame as plight of living with infertility. The moment people start to talk about their children’s performance at school I keep mum. I wonder what is it about for me to discuss, a sullen participant recounted. Another participant who expressed her experience of shame remarked: My husband now knows what the problem is with me. I heard the doctor talked about my blocked womb. Shame may, however, create a feeling of low esteem as experienced by some of the participants.

Anger/Resentment

Frustration due to infertility may evoke anger or resentment in people living with infertility. Sometimes such anger may be directed at pregnant women or those with children. One of the participants aptly remarked: I have stopped attending naming ceremony of newborn even when I am invited. This statement is indicative of anger mixed with jealousy by the participant. In some African societies if an infertile woman, for any reason, expresses anger towards either a fertile woman or her children such infertile woman may suffer reproach. A participant who is the second of her husband’s two wives described what she got while she was provoked by an abusive 8-year-old stepson: I was called a witch even when it could be seen the little boy was throwing abuses at me while his mother (my step wife) looked away.

Hopelessness

Feelings of despondency may arise when treatment efforts seem to be yielding little or no results. Previous infertility treatment of individuals without success results in experiencing severe level of hopelessness.[27] Issues such as lack of social support, dwindling financial resource following huge cost of treatment are factors that may contribute to feeling of hopelessness in infertile women. In this study, none of the nine women with secondary infertility expressed hopelessness. A participant who had fought infertility for 9 years was on the verge of giving up: Every month is more saddening than the previous when the result would come negative. Should I give up wanting children? Hope delayed may result in weariness and doubts about efficacy of treatments may undermine hope. The loneliness of delayed hope may lead to feeling of hopelessness in situation when coping fails. It is of note that about four-fifth of the women in this study did not consider the option of adopting a child to ameliorate the perceived hopelessness. The finding of non-acceptability of adoption as an option for majority of the infertile women supports earlier studies from southeastern and southwestern Nigeria that have shown low level of acceptability.[28,29]

Grief and loss of control

People living with infertility are burdened with experience of grief with feelings of lost opportunities. The diagnosis of infertility in a woman will often lead to grief associated with loss of control[30] which may be manifest as lack of composure. In the course of this study one of the participants who were excluded from analysis actually expressed deep grieving as she was sullen and could not complete the interview. It can be very distressing to an infertile woman when it seems she has lost control over her body. Some infertile woman may lose control to the point of despair. Another of the participant in this study expressed her loss of self-control thus: “I have tried all (referring to previous treatments). I’m back to see a doctor, again.” Really, previous treatment failure may cause renewed cycle of grieving over a child that may never be and causing distress which may manifest as loss of control.[31]

Also of note from this study is the issue of sexual dysfunction as majority of the participants in this study, regardless of coital frequency with spouse described their sexual experience as unsatisfying. This often may occur with associated depression due to infertility state. Findings from some studies would corroborate infertility a potential risk for sexual dysfunction.[32]

CONCLUSION

Infertility can be painful as it affects every aspect of life and relationship of couples living with infertility. It would require a multi-disciplinary approach to relieve the pains, and alleviate the baneful experience of infertile couples. The pains and hurt feelings of infertility are the banes of this seemingly normal part of life. It is worthwhile for people who have no experience of infertility to understand that those who feel it know it. No doubt, the psychological distress of infertility may manifest in couples living with infertility. Regarding the reality of distress and associated experience of psychosocial stressors, it is important, therefore, mental health practitioners are also engaged to participate in the holistic management of infertile couples. The myriads of psychological problems faced by infertile couples are not insurmountable if, and only if, people, including medical practitioners, who do not have challenge of infertility are rather sensitive to the plights of infertile couples.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Comparative study of depression among fertile and infertile women in a South-Western Nigerian city. Medical Journal of Zambia. 2017;44:93-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beliefs and practices to infertility. African Health training Institutions Project 1978:1-15. Unit No 28

- [Google Scholar]

- Men leave me as I cannot have children’: women’s experiences with involuntary childlessness. J Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1663-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infections, pregnancies, and infertility: perspectives on prevention. Fertil Steril. 1987;479:64-968.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infertility and the provision of infertility medical services in developing countries. Human Reproduction Update. 2008;14:605-21. Available from https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn042

- [Google Scholar]

- Infertility in the Gambia: frequency and healthcare seeking. Social Science Medicine. 2008;46:891-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility condition in Gondar, North Western Ethiopia: an appraisal of current states. Studies in Family Planning. 2005;2:110-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The case against new reproductive technologies in developing countries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;103:957-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- The work of a woman is to give birth to children: cultural constructions of infertility in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2013;17:108.

- [Google Scholar]

- ‘Mama and papa nothing’: living with infertility among an urban population in Kigali, Rwanda. Human Reproduction. 2011;26:623-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Change in pattern of marriage and divorce in a Yoruba town. Rural Africana. 1982;14:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes and cultural perspectives on infertility and its alleviation in the Middle East area. In: Vayena E, Rowe PJ, Griffin DP, eds. Current Practices and Controversies in Assisted Reproduction. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploration of infertile couples’ support requirements: a qualitative study. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility. 2015;9:81-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health and traditional care for infertility in the Gambia and Zimbabwe. In: Boerma JT, Mgalla Z, eds. Women and Infertility in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective. Amsterdam, NL: KIT Publishers; 2001. p. :257-268.

- [Google Scholar]

- Men leave me as cannot have children’: women’s experiences with involuntary childlessness. J Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1663-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The experience of infertility: a review of recent literature. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32:140-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic insemination of semen: Ultrasonic monitoring of ovarian follicular growth. Orient Journal of Medicine. 1995;7:32-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2001. Psychosocial characteristics of infertile couples: a study by the ‘Heidelberg Fertility Consultation Service’. Hum. Reprod. 2001;16:1753-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis Scandinavian. Journal of Public Health. 2012;40:795-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infertility and the provision of infertility medical services in developing countries. Human Reproduction Update. 2008;14:605-21. Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn042

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of infertility on the spouses’ relationship. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2012;46:794-801.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infertility and women’s reproductive health in Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 1999;3:7-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bulletin of the World Health Organization: Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility. Available at https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/12/10-011210/en/accessed30/09/19

- Dyadic adjustment and hopelessness levels among infertile women. Cukurova Med J. 2018;43:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and practice towards child adoption amongst women attending infertility clinics in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2011;3:79-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland clinic. Infertility: is it stress related?. Available at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4332-infertility-is-it-stress-related

- 2009. Harvard Mental Health Letter The psychological impact of infertility and its treatment. Available at https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/The-psychological-impact-of-infertility-and-its-treatment

- Sexual dysfunction in women undergoing fertility treatment in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. J Reprod Infertil. 2016;17:26-33.

- [Google Scholar]