Translate this page into:

Reducing dropout rates in ART: A need of hour

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Writing about failures in an inaugural issue is paradoxically unconventional, seldom/ever discussed on any platform, yet is the very pivotal issue, which needs analysis and on a fore front. Infertility is a medical problem, a social taboo devastating not only an individual but the entire family. ART procedures, including in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) do not have a very high success rate and to make it worse still they are surmounted by an equally high dropout rate. So considering the magnitude and sensitivity of the problem, the need for adherence to ART procedures cannot be over emphasized.

We all know that the very high dropout rate in ART, IVF/ICSI in particular, is an indirect consequence of poor outcome of the same and hence the reflection of dissatisfaction bordering on emotional breakdown of the patient. As in the past, time and science will improve the seed and the soil, i.e., the embryo and the endometrium, but the need of the day is to analyze and strategize the often over looked aspects - the non-medical reasons. This will definitely go a long way to reduce the dropout rate and hence increase the cumulative pregnancy rate of IVF. Even if the increase is not by a large margin, it will at least make the actual dropout rate close to that rate which is limited by restrictions of science and the procedure and not due to the non-medical reasons.

No definite consensus is there to define dropout. Generally dropout means no active treatment for a period more than 2 years. Primary dropout is a patient who has opted out in between the treatment and secondary dropout is one who stops treatment after it fails. Even thought it can broadly define dropout, it is a challenging task as there is no clarity as to what constitutes a dropout. This is because dropout is varying variable depending on the country, administrative policies, social pressure, family pressure, educational level and the procedure involved. So, first we should have a consensual definition worldwide keeping in mind the procedure involved, the age of the female, fertility reserve, surrogacy/donor program. Besides true dropout we have to consider false dropout, dropout for individual procedure, dropout at a particular center, and finally over all dropouts.

Reported incidence worldwide ranges from 25-50%. A study from UK reports a dropout rate ranging from 25-42%, increasing with subsequent cycle; Sweden and Netherland report 25-50% dropout rate after 1st cycle.[1] Schroda AK et al. reports that upto 65% couples dropout from IVF before achieving pregnancy before they complete 3 cycle.[2,3] Also, Gleicher et al. reports a larger early dropout rate if patients receive infertility care from generalist rather than specialists.[4]

Other key issues are reasons of dropout, a comparison of our Indian data with the world and look for correctable causes and make policies with greater acceptance. The root cause of this problem are financial, psychological, lack of family support, unrealistic expectations, incomplete information, and perceived lack of staff experience. Limited data is available in this respect and most is from IVF centers from other Western countries. Indian data is negligible.

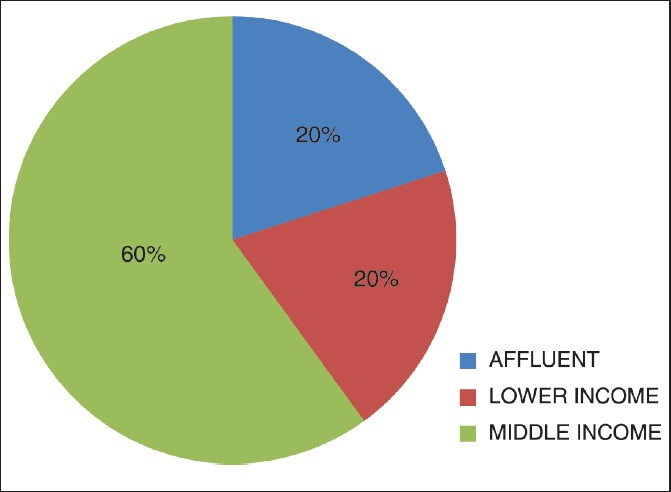

In our series cost was the major constraint; 40% belonged to the middle income group and 20% were from lower income group [Figure 1]. Increased age and poor prognosis patients formed the next major group. At our clinic, in which IVF/ICSI and egg donation/surrogacy is done after critical scrutiny only and many patients who are taken up for IVF have compromised parameters: 40% of patients range from 35-44 years, 40% constitute 30-35 years, and 30% had damaged endometrium from tuberculosis; 40% had poor gametes and 10% had grade iv endometriosis. However, in the Western countries, psychological stress rather than financial was the main reason and the same was reported by other countries the Sweden Netherland and Australia.[5] In Belgium, where upto six cycle are reimbursed, a very high dropout rate was reported signifying the low impact o financial burden.[6] A recent review of 22 studies and 21,453 patients published in Human Reproduction in 2012 found post postponement of treatment in 40%, followed by physical and psycho logical burden in 19% case.[7]

- Income wise distribution of infertile couples

However in India, the major issue is cost as 60-80% of patients belong to middle income and lower income group and there is no insurance coverage and govt. funding is insignificant. In our series, out of 3,250, only two patients received Government funding and that too with great difficulty. In India, the contribution of physical pain and psychological stress is much less, seen only in the affluent class. In rest of the patients, this pain is insignificant to the stress of being tabooed as infertile and beyond treatment. Issue of cost is also a concern in western countries also like Canada and North America, where the ART program is not covered under national health scheme.[8,9] Results from these studies indicate that decision making in infertility treatment is still widely based on financial issues and there is a great divide across the countries based on government health policies.[10]

Even though it is sad, yet paradoxically the silver lining is that with government/insurance sector funding, by formulating acceptable policies we can lower the dropout rate, and that too the primary dropout rate.

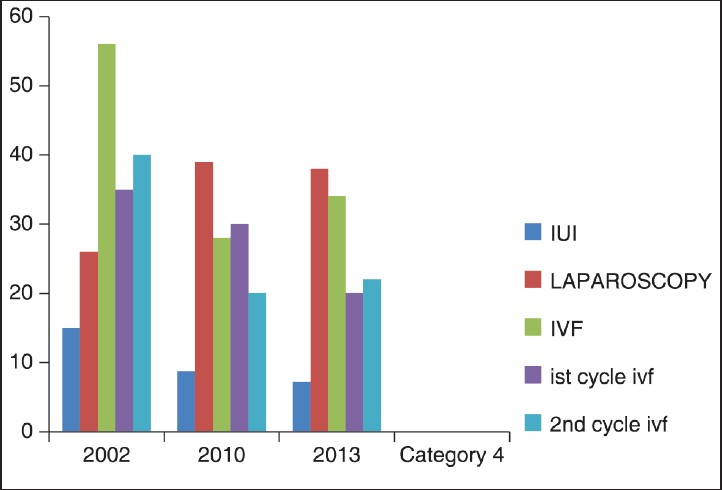

Today Delhi government is offering medical benefit free of cost to below poverty line beneficiaries at its marked clinics. So on parallel lines, the same can be offered to infertility patients at select established ART clinics. Also, it is high time insurance companies step in. They can offer insurance policies to couples against their mortgageable assets. This will significantly reduce the current stress as today couples debate selling their lifetime assets for a procedure which they know has limited success. For this, the media, government, policy makers, social workers, doctors have to come together so to decrease infertility which has plagued the society in a pandemic way. Other factors, like increasing age (40%) poor reserve-poor gametes (40%), the endometrium can be tackled to some extent by optimized IVF stimulation protocols and early referral to dedicated ART clinics and educating the need for the same to the patient. Also in our series, intrauterine insemination (IUI) had the lowest dropout rate, followed by Hystero laparoscopy and IVF /ICSI [Figure 2].

- Dropout Rates - Procedure wise

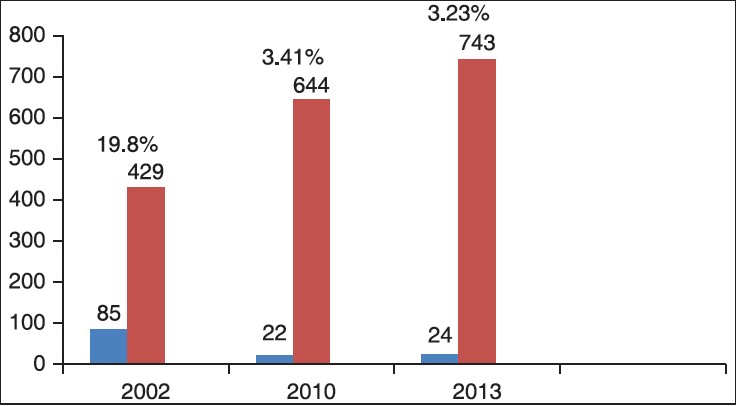

Also noted was the fact that centers with high success rate had decreased dropout rate and this bettered with the experience of clinic [Figure 3].

- Correlation of experience and dropout rates

Another corrective measure is to keep on reviewing the IVF program. The parameter is the good success rate. Yet a center with high success rate is not equated to a good center. A center in which majority of patients are poor risk patients (elderly, poor gamete quality, low reserve, compromised endometrium), the clinician has academic expertise rather than smartness and offers IVF, donor programs after critical scrutiny is unequivocally better than the one in which IVF, donor program are an easy option and majorly of patients enrolled are only good prognosis patients.

Also, there is continuous need to review the IVF program and have quality control. There should be documentation, internal audits, records of non-conformity. In-house expertise of all procedures-be it ultrasonography (USG), lab, andrology work-up, ovum pick-up or fertility-enhancing surgeries should be under one roof. Quality of media/culture and equipments should never be compromised.

Simplified protocols with minimum injections, USG, bioassays, and visits decrease the stress level manifold.

Also set realistic expectations. Patients should be counseled in detail for long treatment and limitations of procedures so they are prepared for multiple cycles if first cycle fails, to achieve pregnancy.

Also offer education (through text, web) and support them throughout the infertility journey. Communication should be available, 24/7 telephone connectivity, and a patient redressal system. Intensive nursing care for supporting the emotionally drained patient.

CONCLUSION

Dropout in IVF is mainly related to stress. Reducing stress will improve adherence and decrease dropout. As cost is a major factor in discontinuation, cost-reduction strategies should be evolved to reduce discontinuation. Thorough counseling, especially of the limitations of procedures and educating your patients about failures go a long way to reduce dropouts. Moreover, one should make IVF patient friendly. It is the joint responsibility of the society, government, industrial sector, medical profession, and media to make efforts for reducing dropout rates by education, cost reduction, physiological support, and quality control.

Source of Support:

Nil

Conflict of Interest:

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Reasons for discontinuation of IVF treatment: A questionnaire study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:358-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient dropout in assisted reproductive technology program: Implication for pregnancy rates. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2651-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient dropout in an assisted reproductive technology program: Implication for pregnancy rates. RBM Online. 2004;5:600-06.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infertility treatment dropout and insurance coverage. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:289-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reasons for dropout in infertility treatment. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68:58-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of psychological distress in patients starting IVF treatment: Infertility-specific versus general psychological characteristics. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1471-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18:652-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing patients' decision not to repeat IVF. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1997;14:381-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of not pursuing infertility treatment after an infertility diagnosis: Examination of a prospective U.S. cohort. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2369-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- International disparities in access to infertility services. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:871-5.

- [Google Scholar]