Translate this page into:

The impact of endometrial scratching on the outcome of in vitro fertilization cycles: A prospective study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rita Bakshi, International Fertility Centre, H-6, Green Park Main Market, New Delhi 110017, Delhi, India. E-mail: ritabakshi.ifc@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

Local endometrial trauma (endometrial scratch) is a treatment strategy to improve implantation rates. The objective is to study the relation of endometrial scratching in case of in vitro fertilization.

Design:

A randomized retrospective study was conducted to know the effects of endometrial scratching on the results of IVF procedure.

Materials and Methods:

Source of data: This study is undertaken at the International Fertility Centre, New Delhi, with patients with infertility undergoing IVF cycles. Method of collection of data (including sampling procedure if any): All diagnosed cases of primary and secondary infertility requiring IVF are enrolled in the study. A detailed history and clinical evaluation is done. Information is collected in a pretested proforma. Inclusion criteria: All diagnosed cases of primary and secondary infertility requiring self-egg IVF, who came to the OPD of International Fertility Centre, New Delhi. The group in which endometrial scratching preceded the IVF cycle was selected randomly irrespective of socioeconomic status, BMI, or any other factors. The cases and controls were of the same age group. Exclusion criteria: All cases of natural conception or IUI case. Statistical analysis: Following statistical methods are employed in the present study – contingency table analysis and Chi-square test.

Results:

(1) Endometrial scratching is statistically significant on 1st cycle of IVF outcomes. (2) Success of endometrial scratching in cases of recurrent implantation failure is statistically not significant. (3) Success rate of endometrial scratching in primary infertility cases is statistically not significant. (4) Success rate of endometrial scratching in cases of secondary infertility is statistically not significant.

Conclusion:

Endometrial scratching is statistically significant on 1st cycle of IVF outcomes. It is postulated that local endometrial injury in stimulated cycles delays endometrial development due to the wound repair process and thereby corrects the asynchrony between the endometrial and embryo stages.

Keywords

Endometrial injury

implantation rate

in vitro fertilization

intra cytoplasmic sperm injection

INTRODUCTION

Implantation remains a limiting step in in vitro fertilization (IVF) as well as intra cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Many procedures have been tried to improve the implantation rate in IVF/ICSI cycles. Endometrial injury is one of these procedures that has gained popularity in the past few years. However, the underlying mechanism through which endometrial injury improves implantation is still unclear. There are three main supposed theories. The first theory suggests that the mechanism involves inducing decidualization of the endometrium, which might improve the implantation of the transferred embryos.[1] The second theory suggests that the process of healing after endometrial injury involves an inflammatory reaction mediated with cytokines, interleukins, growth factors, macrophages and dendritic cells, which are beneficial to embryo implantation.[1,2,3]

The third theory suggests that endometrial injury in a previous cycle leads to better synchronicity between the endometrium and transferred embryos through retarding endometrial maturation.[1]

In this trial, the aim was to (a) assess the effectiveness and safety of endometrial injury in a previous cycle in patients undergoing first IVF/ICSI cycle, (b) assess the effectiveness of endometrial injury in patients with RIF and (c) assess the effectiveness of endometrial injury in patients with primary and secondary infertility undergoing IVF cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a prospective randomized controlled trial involving for 336 patients undergoing IVF/ICSI at an IVF unit (International Fertility Centre, New Delhi) from February 2017.

All the patients provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Inclusion criteria were the following:

All patients diagnosed with primary and secondary infertility requiring self-egg IVF, who presented to the OPD of the International Fertility Centre, New Delhi. The patient in whom endometrial scratching preceded the IVF cycle was selected randomly irrespective of her/his socio-economic status, BMI or any other factor. The cases and controls belonged to the same age group (25–40 years).

FSH levels ≤12.

A normal uterine cavity determined by hysteroscopy (performed routinely for all cases prior to ICSI).

≥2 good-quality embryos to be replaced.

The exclusion criteria were the following:

Age >40 years.

All patients with natural conception or patients undergoing IUI.

Patients with an abnormal uterine cavity due to submucous fibroid, endometrial polyps, Asherman’s syndrome or congenital uterine malformations.

Patients who had <2 good-quality embryos at the time of transfer for analysis.

The following investigations were performed:

CBC with HPLC.

Husbands semen analysis (HSA).

Serum anti Mullerian hormone (S. AMH).

Antral follicle count (AFC) and transvaginal sonography (TVS) for the uterine cavity.

Analysis of the husband’s semen.

Randomization

The study was explained to all eligible patients. They were offered participation in study and were, therefore, given a patient information sheet. They were given enough time to make a decision on their participation. After undergoing hysteroscopy, those who were accepted to take part in the study gave an informed consent form. Randomization was done by simply using sealed envelopes before the patients underwent hysteroscopy.

Hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity

Hysteroscopy was performed in all patients as per the unit protocol in the cycle preceding the ICSI cycle. The hysteroscope used in the study was a rigid continuous flow panoramic hysteroscope with 30° fiberoptic lens. Hysteroscopy was performed 2–5 days postmenstrual and without anaesthesia.

Endometrial sampling

In the intervention group, endometrial sampling was performed once between the 21st and 24th days of the non-transfer cycle at an outpatient clinic. Endometrial sampling was performed using Pipelle endosampler catheter (MedGynEndosampler, MedGyn Products Inc., USA) [Figure 1]. The fundus and the posterior wall of the uterine cavity were scratched three times. No antibiotics were prescribed to patients after the procedure.

- Pipelle endosampler catheter

Treatment protocol

Individualized protocols for both down-regulation and controlled ovarian stimulation were used. GnRH agonist mid-luteal protocol was used for patients aged ≤35 years, with FSH levels <10, and AFC ≥10. Antagonist protocol was used for patients aged >35 years, with FSH levels ≥10 and AFC <10. In the long agonist protocol, patients were down-regulated with 0.1 mg Decapeptyl, which was given by subcutaneous injection (Decapeptyl, Ferring, Germany).

The dose was then reduced to 0.05 mg and continued till the day of HCG administration. In the antagonist protocol, the GnRH antagonist was given when a leading follicle reached a size of 14 mm and was continued till the day of HCG administration. Gonadotropin stimulation was started on day 2 or 3 of the cycle after confirming pituitary desensitization. The starting dose of gonadotropins was chosen on the basis of age, BMI, AFC and prior response to gonadotropin stimulation as per unit protocol. Exogenous gonadotropins used were in the form of human menopausal gonadotropins (HMG). Ovarian follicular responses were monitored with transvaginal ultrasound. Ultrasound scanning was started on day 5 of stimulation, and then performed every other day. HCG injection was given when at least three follicles greater than 16 mm in diameter were detected on transvaginal ultrasound scan, with the leading follicle having reached 18–20 mm in diameter. Oocyte retrieval was performed under anaesthesia 36 h after HCG administration. Insemination was performed by standard ICSI method. Embryos were classified according to Veeck’s grading[4] as follows:

Grade 1: Pre-embryos with blastomeres of equal size and no cytoplasmic fragmentations.

Grade 2: Pre-embryos with blastomeres of equal size with cytoplasmic fragmentations equal to 15% of the total embryo volume.

Grade 3: Uneven blastomeres with no fragmentations.

Grade 4: Uneven blastomeres with gross fragmentation (≥20% fragments).

Cleavage-stage embryo transfer (ET) was performed on day 3. ET was performed under an abdominal ultrasound guide for proper embryo placement to the mid-uterine cavity. Two to five grade 1 or 2 embryos were transferred as per unit protocol. ET was performed with Wallace catheter (Smith Medical International Ltd., Hythe, Kent, UK). Progesterone support for the luteal phase was commenced on the day of ET with 800 mg micronized progesterone vaginally administered till 12 weeks of pregnancy. Serum HCG pregnancy test was performed 14 days after ET. Ongoing pregnancies were confirmed by the presence of at least one viable foetus, which was ultrasonographically confirmed, within the uterus 4 weeks after ET.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures of the study were determined on the basis of the following parameter:

Implantation rate: calculated as the number of gestational sacs evident by ultrasound divided by the number of transferred embryos.[5]

The secondary outcome measures of the study were determined on the basis of the following parameters:

Clinical pregnancy rate: calculated as the number of patients with clinical pregnancy (by the detection of foetal heart beat with an ultrasound scan) divided by the number of patients who underwent ET.

Miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy: calculated as the number of patients who had a miscarriage (<24 weeks) divided by the number of patients who had clinical pregnancies.

Multiple gestations rate: calculated as the number of patients who had multiple gestation divided by the number of patients who had clinical pregnancies.

Pain: pain reported during the intervention..

Bleeding: reports of abnormal bleeding during or after the intervention.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 17 software for Microsoft Windows. Data were described in terms of mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for continuous variables and frequencies (number of cases) and as percentages for categorical data. Chi-square test was used to compare the categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

This prospective study initially included 361 eligible participants. A total of 22 patients refused to take part in the study. Three patients were excluded from the intervention group, because they experienced severe pain during the procedure, and therefore, endometrial scratching was discontinued. Apart from these three patients, no other patient reported moderate or severe pain during the procedure. None of the patients reported infection or heavy bleeding after the procedure. There was no disturbance in the menstrual cycle other than minimal vaginal spotting for a few days after the procedure.

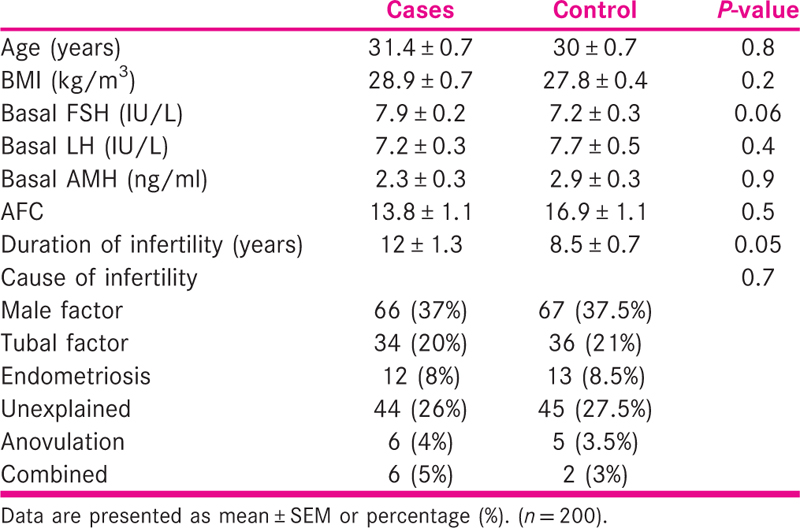

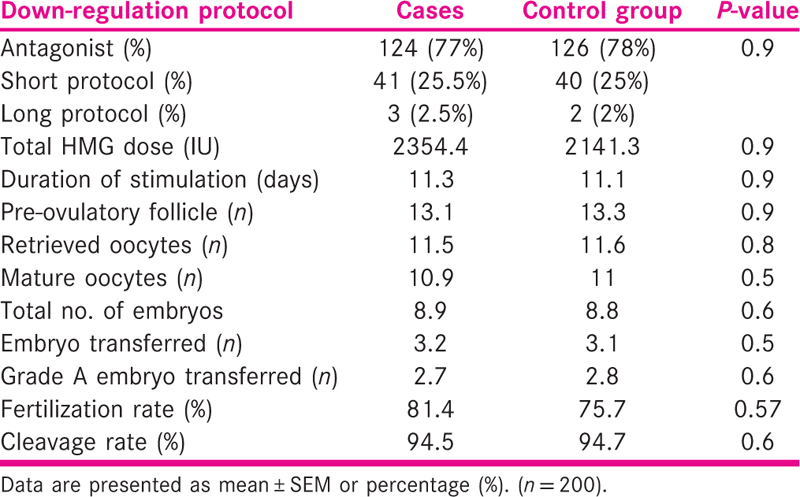

There was no significant difference between the case and control groups regarding chronological age, BMI, duration and causes of infertility, AFC and baseline hormonal profile. The details regarding this are shown in Table 1.

The details of ovarian stimulation are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to down-regulation protocol used, total dose and the duration of gonadotropin stimulation, the number of pre-ovulatory follicles, the number of retrieved oocytes, fertilization and cleavage rates and the number of grade A transferred embryos.

-

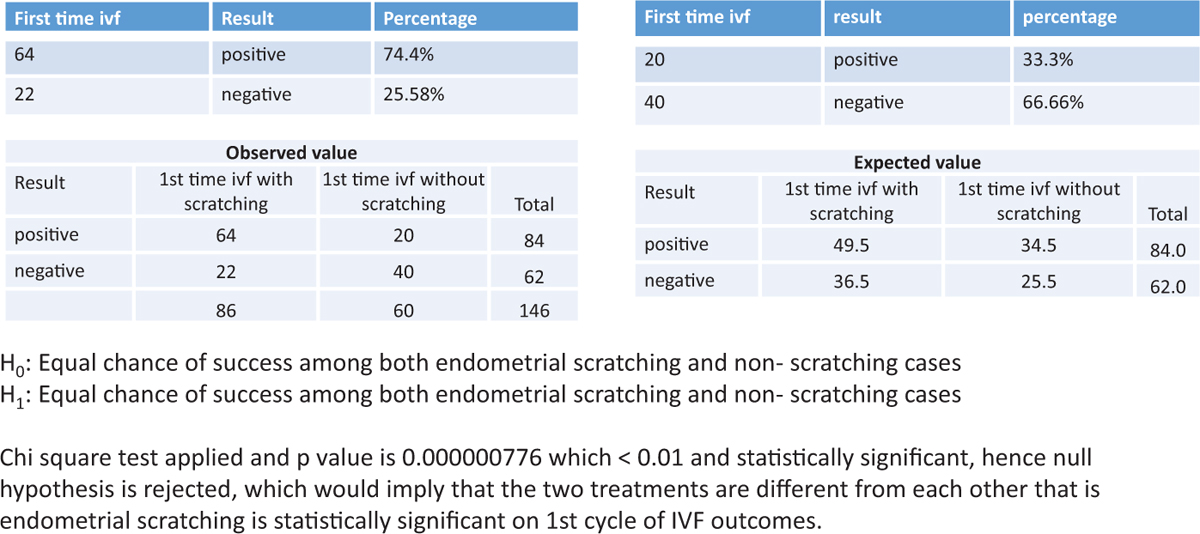

Endometrial scratching was statistically significant on the 1st cycle of IVF outcomes. (P value was 0.000000776, which was <0.01 and statistically significant.) The details are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2- The success rate of scratching in patients undergoing the 1st cycle of IVF

-

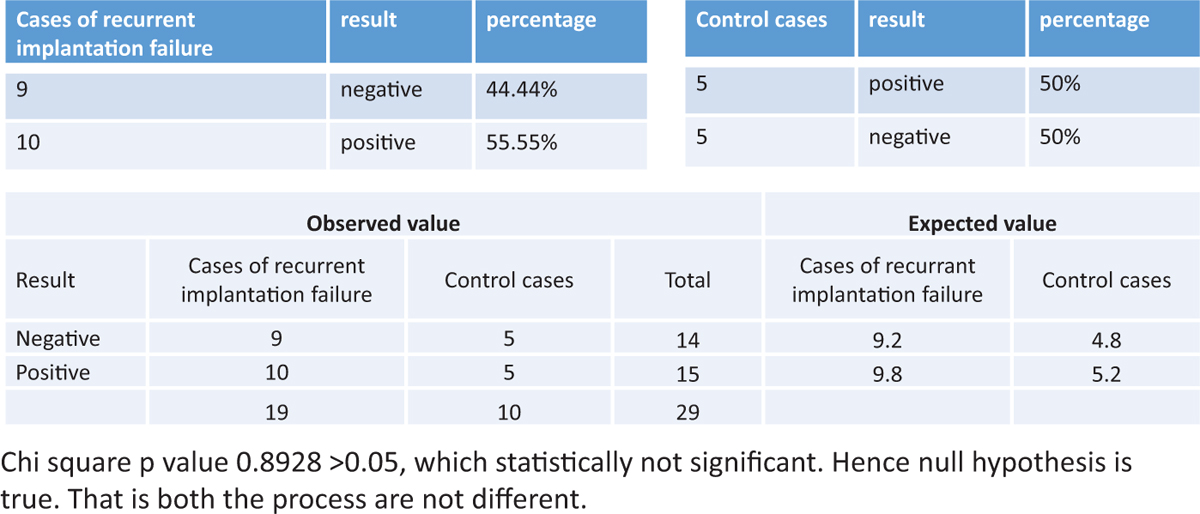

The success rate of endometrial scratching in patients with recurrent implantation failure was statistically not significant. (P value was 0.8928 >0.05, which was statistically not significant.) The details are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Figure 3- The success of endometrial scratching in patients with recurrent implantation failure

-

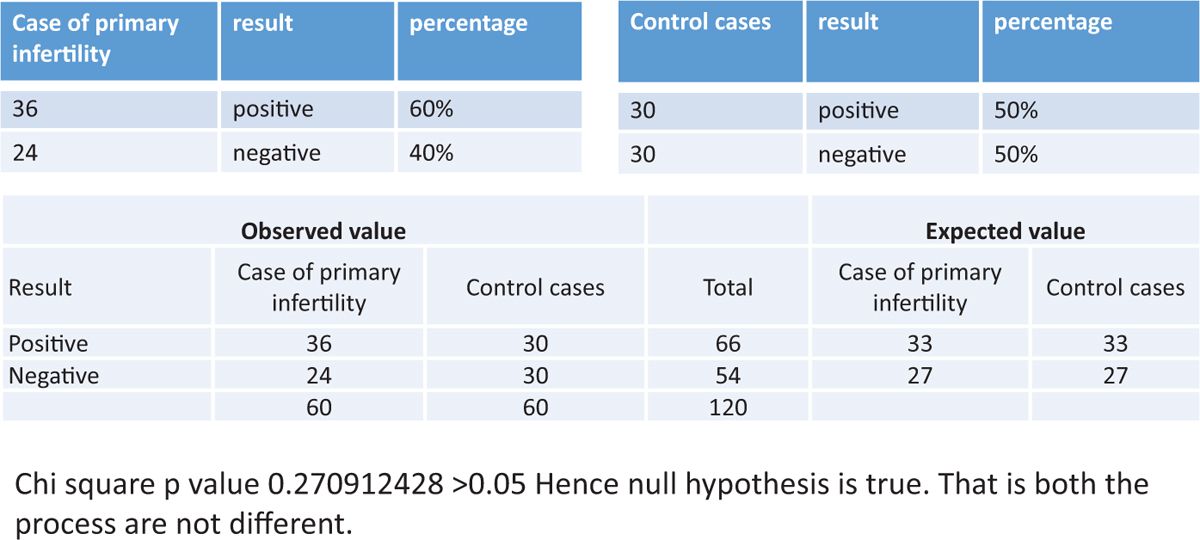

The success rate of endometrial scratching in patients with primary infertility was statistically not significant. (P value was 0.270912428 >0.05.) The details are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Figure 4- The success of endometrial scratching in patients with primary infertility

-

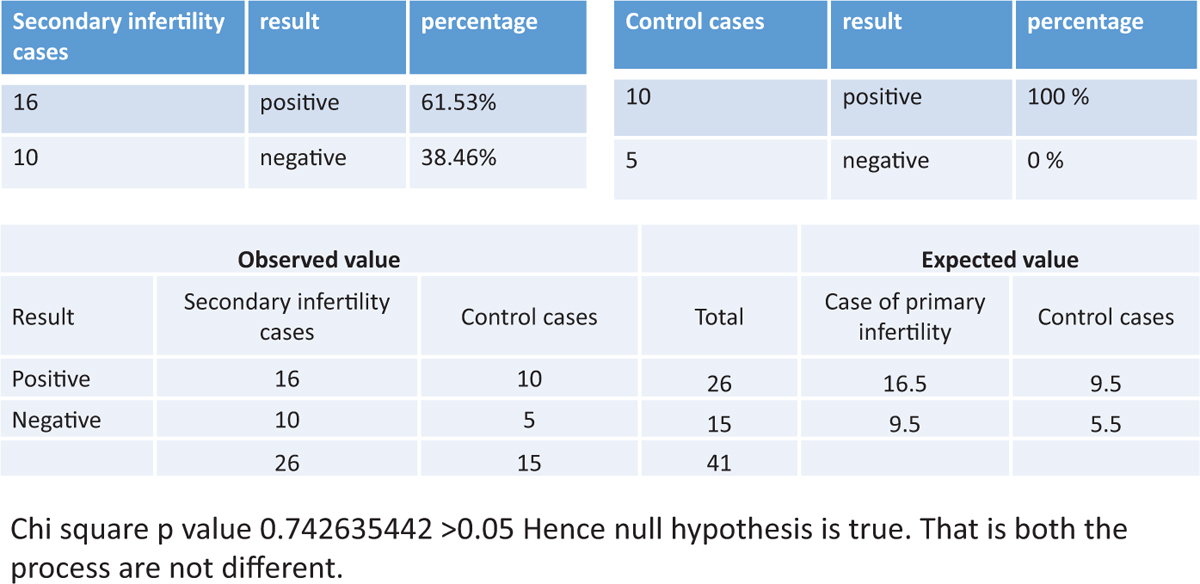

The success rate of endometrial scratc hing in patients with secondary infertility was statistically not significant. (P value was 0.742635442 >0.05.) The details are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Figure 5- The success rate of endometrial scratching in patients with secondary infertility

Primary outcome measures

The implantation rate was significantly higher in the intervention group when compared with the control group (74.4% vs. 25.58% and 33.3% vs. 66.6%, respectively).

Secondary outcome measures

The clinical pregnancy rate was significantly higher in the intervention group when compared with the control group.

DISCUSSION

Implantation failure remains the main obstacle to IVF/ICSI success. Many trails had been conducted to improve implantation. One of most promising methods is to induce endometrial injury during the luteal phase of the proceeding cycle that precedes the stimulation cycle. Although the underlying mechanism of how endometrial injury improves endometrial receptivity remains unclear, an inflammatory action is usually suggested.

In this trial, the aim was to (a) assess the effectiveness and safety of endometrial injury in a previous cycle in patients undergoing first IVF/ICSI cycle, (b) assess the effectiveness of endometrial injury in patients with RIF and (c) assess the effectiveness of endometrial injury in patients with primary and secondary infertility undergoing IVF cycle.

In the current study, hysteroscopy was performed in a separate setting during the follicular phase of the preceding cycle, because that allowed a better evaluation of the cavity and the exclusion of patients with intra-uterine abnormality. In a recent study, hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy were performed at the same time in the luteal phase.[6] Minor endometrial abnormality might be obscured by the thick endometrium present during the luteal phase; therefore, performing a hysteroscopy was not feasible at this time. In our study, single endometrial injury with Pipelle biopsy catheter was shown to significantly improve the implantation rate, as well as the clinical pregnancy rate in patients undergoing IVF/ICSI.

To our knowledge, only one trial included women subjected to their first IVF/ICSI cycle.[7] However, in that study, endometrial injury was performed at the time of ovum pick up, and that was associated with a significant reduction in the clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates. Such an observation was most properly due to the disruption of the growing endometrium at the critical time of IVF/ICSI cycle. Previous studies that evaluated endometrial injury included either patients with previous implantation failure or included women regardless of the number of previous IVF attempts.[6,8,9,10,11,12] Except for the study conducted by Karmizade et al., all other studies reported improvement in IVF/ICSI outcome with endometrial injury.[7]

There is no consensus regarding the optimal number of endometrial injuries. In our study, we performed the endometrial injury once between day 21st and day 24th of the preceding cycle. In some studies, endometrial injury was performed only once, as in our study.[6,7,9,11] Endometrial injury was performed twice in several other studies.[3,10] There is also no consensus regarding the best time to perform as endometrial injury. There are some suggestions that endometrial injury performed during the luteal phase was more likely to induce decidualization. Further studies are needed to compare the effect of single vs. repeated endometrial injuries on IVF/ICSI outcome and to determine the best time of the cycle to induce endometrial injury.

A recent meta-analysis that included 901 patients from eight studies concluded that endometrial injury performed before the IVF treatment cycle was associated with significant improvement in outcome, and there was a need for a well-conducted randomized study to confirm those findings.[11] Similar conclusions were drawn by a systematic review conducted on 2062 patients from seven studies.[12] A recent Cochrane review performed on 591 patients from five trials reported similar conclusions and addressed the need for large studies to address the beneficial effect of endometrial injury prior to IVF/ICSI.[13] The results of our study will be helpful in supporting the concept regarding the need for endometrial injury, which should be performed as a routine procedure prior to IVF/ICSI treatment cycle, and not only in patients with previous implantation failure.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, endometrial injury induced by Pipelle biopsy sampling is a safe and simple outpatient procedure associated with significant improvement in implantation, as well as the clinical pregnancy rate in patients undergoing IVF/ICSI. We recommend that the procedure be performed routinely in all patients undergoing IVF/ICSI in the non-transfer cycle.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the entire medical, laboratory and nursing staff of the International Fertility Centre, as well as for their kind support in the course of the study.

REFERENCES

- Local injury to the endometrium: Its effect on implantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;21:236-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human tumor necrosis factor: Physiological and pathological roles in placenta and endometrium. Placenta. 2009;30:111-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2030-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The morphological assessment of human oocytes and early conception. In: Keel BA, Webster BW, eds. Handbook of the Laboratory Diagnosis and Treatment of Infertility. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. p. :353-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary on ART terminology. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2683-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of luteal phase hysteroscopy and concurrent endometrial biopsy on subsequent IVF cycle outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:269-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Local injury to the endometrium on the day of oocyte retrieval has a negative impact on implantation in assisted reproductive cycles: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;281:499-503.

- [Google Scholar]

- Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1317-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial local injury improves the pregnancy rate among recurrent implantation failure patients undergoing in vitro fertilisation/intra cytoplasmic sperm injection: A randomised clinical trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49:677-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does local endometrial injury in the nontransfer cycle improve the IVF-ET outcome in the subsequent cycle in patients with previous unsuccessful IVF? A randomized controlled pilot study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3:15-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial injury and outcome of the subsequent IVF cycle. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2001;96(Suppl):S277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial injury to overcome recurrent embryo implantation failure; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2012;25:561-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD009517.

- [Google Scholar]