Translate this page into:

Seminal plasma cadmium/zinc ratio among nonoccupationally exposed men investigated for infertility

Address for correspondence: Prof. Mathias Abiodun Emokpae, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria. E-mail: mathias.emokpae@uniben.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

The declining trend of male reproductive health in recent times has raised concern among investigators and the contribution of environmental toxicants to this public health disorder has not been sufficiently evaluated in our setting.

Objective:

To evaluate the seminal plasma levels of lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), and serum testosterone of nonoccupationally exposed infertile males.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 70 infertile males investigated for infertility and 50 men of proven fertility were evaluated. The seminal plasma Pb, Cd, and Zn levels were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Buck Scientific Model VGP-210, Germany), while the serum testosterone was assayed by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique using reagent supplied by Diagnostic Products Monobind Inc. Lake Forest, CA 92630, USA). Semen analyses were performed using standard techniques as recommended by the World Health Organization. The results were compared between infertile and fertile groups using unpaired Students t test.

Results:

Mean seminal plasma Pb, Cd, and Cd/Zn ratio were significantly higher (P<0.001) in infertile males than controls. Cd/Zn ratio (r = −0.242; P<0.04) correlated negatively (P<0.001) with serum testosterone. Mean serum Zn level was significantly lower (P<0.001) in infertile men than controls, but the difference in the level of serum testosterone was not significant (P<0.415).

Conclusion:

Evaluation of seminal plasma Cd, Pb, Zn, and Cd/Zn ratio may be considered in a comprehensive investigation of the infertile men while informed risk modeling to preventing exposure to toxic metals may help to mitigate their health consequences.

Keywords

Seminal plasma

cadmium

zinc

male infertility

INTRODUCTION

The declining trend of male reproductive health since the past few decades has raised concerns among investigators all over the world. The situation is more worrisome in the so-called infertility belt of sub-Saharan Africa.[1] Although many factors such as lifestyle, stress, sexually transmitted infections, and obesity are believed to be responsible for declining semen quality, environmental toxicants are thought to play a significant role in deteriorating male reproductive health.[2]

The sexual accessory glands secrete several elements such as enzymes, lipids, macro, and micro-elements into the seminal plasma, which are met for the development and physiological functions of spermatozoa. Zinc (Zn) is very important for optimal physiological functions such as growth, reproduction, DNA synthesis, cell division, gene expression, wound healing, and immune system.[3,4,5]. Zinc is reported to be higher in seminal plasma than blood because of the several roles it plays in the sperm’s functional properties. Examples of such roles include anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, lipid flexibility, and sperm membrane stabilization, aid spermatozoa capacitation, acrosome reaction, and embryo implantation.[6,7]. According to the World Health Organization estimates, one-third of the world population is deficient in Zn. Africa, South Asia, and Western Pacific are the most affected regions.[8] Despite the high prevalence of Zn deficiency in humans, less attention has been given to its impact on male fertility potential.[9] Male infertility is influenced by Zn because of the several physiological roles in testicular development, spermatogenesis, and sperm quality.[10,11].

Cadmium (Cd) is a ubiquitous environmental pollutant that possesses a risk to human health. It is of concern because almost everybody in the general population is exposed in one or the other to the toxic metal via food supply and environmental exposure.[12] The toxic metal can accumulate in the body over a lifetime and negatively impact reproduction. It was recommended that mitigating efforts should be implemented to reduce the risks associated with Cd exposure.[12]. Toxic effects of Cd action come from interactions with essential elements such as Zn. These interactions occur at different stages; absorption, distribution, and excretion of both metals as well as at the sites of biological function.[13,14]. Exposure to Cd can results in the disturbance of Zn concentration while dietary Zn intake also affects Cd absorption, accumulation, and toxicity. Therefore, adequate Zn levels in the body can mitigate Cd toxicity while Zn deficiency enhances Cd accumulation and toxicity.[13].

Studies in parts of Nigeria indicate that Cd concentrations are high in the soil, food, and water[15,16], and food is grown on soil that contains high levels of Cd is a potential human health risk as a result of transmission in the food chain.[12,17]. Our group previously reported higher Cd and lower Zn levels in the seminal plasma of infertile men.[18]. The impact of several mitigating measures to preventing the adverse reproductive health consequences of Cd toxicity requires periodic evaluation. This study seeks to determine the seminal plasma levels of Cd, Zn, Cd/Zn ratio, and their associations with serum testosterone levels in men investigated for infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This is a cross-sectional study of males investigated for infertility in tertiary fertility clinics in Benin City. The study participants were between the ages of 25 and 45 years and comprised of 70 consecutive subjects who met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated for infertility because their partners were unable to conceive after one or more years of unprotected intercourse. The control group comprised of males without chronic clinical illnesses and had their baby within the last 1 year.

Sample size determination

The sample size (N) was determined using the sample size determination formula for health studies[19] and 4.0% prevalence of male infertility in Ilorin.[20]

N = 59 minimum sample sizes

Therefore a minimum of 70 test samples and 50 controls was used for this study.

Ethical consideration

All study participants were enlightened on the nature of the study and informed consent was obtained before specimens were collected. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics committee of the Edo State Ministry of Health (Reference number: HM.1208.355; dated: 26th October 2017).

Inclusion criteria

All male subjects aged 25 to 45years evaluated for infertility and consented to be enrolled without physical abnormalities or chronic illnesses were included in the study. They had no history of trace element supplementation in the last six months. Subjects without chronic clinical illnesses and had their babies within the last 1 year, whose seminal fluid analysis showed over 15 million sperm cells per milliliter semen according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria were included and used as controls,[21].

Exclusion criteria

Individuals with known pathological or congenital conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, sexually transmitted diseases, testicular varicocele, and genital warts were excluded. Besides, individuals currently on antioxidant supplementation, smokers, alcoholics, and those with known endocrine disease and physical abnormality were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Qualitative data were collected using a semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires consisted of three sections with open-ended questions and probes aimed at exploring the socio-demographic profile. Section A (Socio-Demographic characteristics), Section B (Exposure, awareness, and protection), and Section C (Medical/family history). The questionnaire was distributed among the study participants.

Sample collection

Semen samples were collected in a sterile trace element-free container by self or assisted masturbation after at least 72 hours of sexual abstinence (without the use of spermicidal lubricants). The specimens were delivered to the laboratory within 30 minutes of ejaculation. Two specimens were collected at different visits within 2 months for analysis and the mean value of the determinations was used. This is because spermatozoa are specialized cells that exhibit a diverse array of biological characteristics. The semen analyses results could be subjective and prone to intra and inter-observer variability. Also, the sperm quality of an individual can vary widely due to the duration of abstinence from coitus, febrile illness stress, and method of specimen collection. A blood sample was also collected the same morning semen was submitted. Five milliliters of blood was collected in a plain container. This was allowed to clot and serum separated after centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The serum was kept at −20°C until analysis was done.

Routine semen analysis

After the liquefaction, the semen specimens were assessed for volume, appearance, pH, and viscosity. Routine semen analysis was performed microscopically with a special interest in sperm concentration, % motility, and % morphology. Based on the sperm concentration/count according to WHO criteria,[21] the overall samples were therefore grouped into the following categories: 20 normospermia; ≥ 15 million sperm cells per milliliter semen, 30 oligozoospermias; ≤ 15million sperm cells per milliliter semen, and 20 azoospermia; absence of sperm cells in the ejaculate. Thereafter, samples were centrifuged and the supernatant seminal fluid was separated into another trace element-free clean and sterile plastic container. The seminal fluid plasma was then stored at −20C before assay of measured variables within 2 weeks.

The seminal fluid CD, Pb, and Zn was determined by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer and serum testosterone was assayed by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique using reagent supplied by Monobind Diagnostics Inc, Lake Forest, CA USA.

Measurement of cadmium, lead, and zinc

The seminal fluid Cd and Pb were assayed using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) (Buck Scientific Model VGP-210, Germany). Exactly 2 mL of each sample were digested with a mixture of 4 mL HNO3 and H2SO4 (ratio 4:1) and heated 4 hours daily slightly in a water bath at a temperature of 80C to ensure complete digestion. The digested samples were then taken for AAS analysis. The metal content of the digested samples was determined by aspiration (air/acetylene flame) using atomic absorption spectroscopy at appropriate wavelengths of 217.0 nm and 228.8 nm for Pb and Cd, respectively. For seminal fluid zinc assay was done by diluting seminal fluid 1:4 with de-ionized water/nitric acid and analyzed using AAS. Certified Cd, Pb, and Zn reference solutions for atomic spectrometry were used as controls (Sigma-Aldrich Co, LLC, USA). Intraindividual variability was controlled by ensuring that samples were analyzed in duplicates and the sample mean was used for statistical analysis. Similarly, the analyses were done by the same person to avoid inter-individual variation.

Statistical analysis

Data from the study were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0 software (SPSS Chicago, IL, USA). The comparisons of mean values of measured parameters between infertile males and controls were performed using unpaired student t test, Categorical data were compared using Chi-square and Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used correlate measured elements with serum testosterone. The statistical significance level was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Results obtained were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The mean age of study participants was 40.78 ± 6.60 while the mean age of the control subjects was 40.28 ± 6.10.

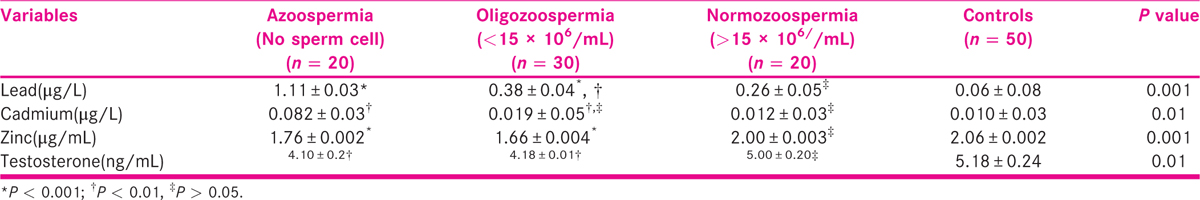

Table 1 shows the mean concentration of seminal plasma Cd, Pb, Zn, and serum testosterone levels in infertile males and control subjects. Seminal lead, Cd levels, and Cd/Zn ratio were significantly higher in infertile males (P < 0.001) than with controls while seminal plasma zinc was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in infertile males than control subjects but the difference in serum testosterone between infertile and control subjects was not significant (P < 0.415).

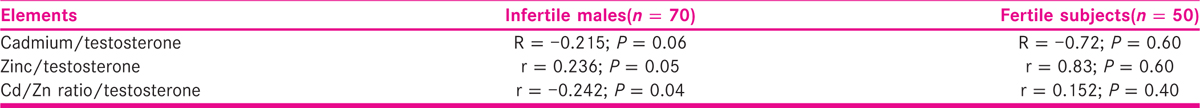

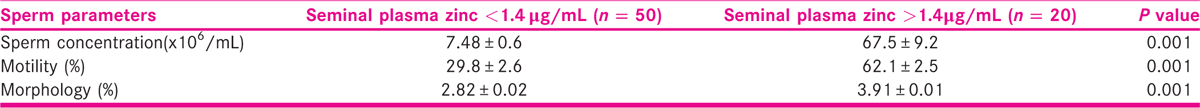

Table 2 shows the mean concentrations of seminal plasma lead, Cd, Zn, and serum testosterone among azoospermia, oligozoospermia, normozoospermic, and control subjects. The seminal lead was significantly (P < 0.001) higher in azoospermic men than oligozoospermic and normozoospermic men, whereas values in oligozoospermic, when compared with normozoospermic men, were significantly higher (P < 0.01) than control subjects. Seminal Cd level was significantly higher (P < 0.01) in azoospermic men than oligozoospermic, normozoospermic and control subjects, whereas values in oligozoospermic, normozoospermic men and control subjects were not significantly different. Serum Zn level was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in azoospermic and oligozoospermic when compared with normozoospermic men and control subjects. Seminal plasma Cd/Zn ratio inversely correlated (r = −0.242; P < 0.04) with serum testosterone concentrations while seminal plasma Zn (r = 0.242; P < 0.04) correlated positively with and serum testosterone concentration (Table 3). Table 4 shows the effect seminal plasma Zn concentrations on measured sperm indices among study participants. Sperm concentration, motility, and morphology were significantly (P < 0.001) lower among males with seminal plasma Zn less than 1.4 μg/mL than those with seminal plasma Zn greater than 1.4 μg/mL. Table 5 shows that age of study participants had no significant effect on seminal plasma levels of Pb, Cd, and Zn.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of male factor infertility has a tremendous impact on the physical and emotional health and quality of life of affected couples. The decline in semen quality over the past 60 years has become a public health challenge all over the world. This is particularly important in the so-called infertility belt of sub-Saharan Africa.[22]. The proportion of infertile men in our setting may be larger than reported and this may limit the opportunities for patient education about the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of male infertility.[23]. This is so because men are less likely to pursue medical evaluation than women, probably due to social reasons, fear, cultural norms, or lack of health insurance coverage.[23]. Also, not much attention is paid to male infertility by both governments and donor organizations rather more funds are donated toward birth control than infertility in Nigeria.

This study evaluated the levels of seminal plasma Pb, Cd, Zn, and serum testosterone among infertile males who are not occupationally exposed to toxic metals. The overall results of this study indicate that the concentrations of Cd, Pb, and Cd/Zn ratio was significantly higher while zinc and serum testosterone levels significantly were lower among infertile men than control subjects. This is in agreement with previous studies.[18,24,25,26]. Several environmental factors have been associated with the risk of male infertility.[27]. Cadmium has been recognized as an endocrine disruptor by binding to androgen and estrogen receptors thereby inhibiting steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis, which may affect semen quality.[28,29]. Cadmium and lead are two well-known toxic metals to which humans are exposed either occupationally or environmentally. They impact negatively on male fertility potentials.[30]. They are present in the environment and accumulate in the body over a lifetime.[31]. Toxic metals have the potential to induce oxidative stress via disruption of the lipid membrane, and spermatozoa rich in poly-unsaturated fatty acids are readily susceptible to oxidative damage. Cadmium is a nonessential trace element that does not contribute to the growth of humans and plants.[32,33], but plays an antagonistic role to zinc utilization, induce oxidative stress, impair p53 protein suppression of cancer and modification of DNA repair.[34,35]. Human beings are exposed to Cd via food intake, drinking water, contaminated soil, inhalation of tobacco smoke, or particulate matter from ambient air.[36].

Cadmium has been reported to affect sex hormone levels, a situation that was attributed to the effect of Cd on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis outside the Leydig cells.[37]. Cadmium is capable of entering the chromatin of developing spermatozoa and also affects microtubules and mitochondrial function of sperms which may explain the adverse effect on sperm quality.[38]. Cadmium has been reported to have a toxic effect on many enzymes dependent on iron as a co-factor, one of these being cytochrome P450[39], and Leydig cells are reported to contain ten times more of P450 than Sertoli cells. This may explain why it is more sensitive to increased Cd level. It should be noted that cytochrome P450 is required for the adequate function of 17-α-hydroxylase, a key enzyme in the steroidogenic pathway that produces androgens; its disruption may well interfere with testicular steroidogenesis, consequently reduced fertility.[26].

The study participants had no history of occupational exposure to Cd and lead. This is an indication that low-level exposure to environmental toxic metals may be implicated in the poor semen quality. It was earlier reported that environmental Cd and lead exposure levels depending on duration may lead to disruption of both hypothalamus and pituitary glands functions in both experimental animals and humans which may result in hormonal imbalance and hence poor spermatogenesis and sperm development.[40]. This may account for the observed association between Cd/Zn ratio with serum testosterone. A significant association was previously observed between Cd, Pb, and sperm quality by our group.[18,26].

The role of increased seminal plasma Cd levels is poorly understood in occupationally unexposed males.[28]. In experimental studies, it was reported that testicular dysfunction was the major finding when cadmium was injected into mice. It was observed that environmental Cd and Pb exposure levels depending on duration may lead to disruption of both hypothalamus and pituitary glands functions in both experimental animals and humans which may result in hormonal imbalance.[40], hence the significantly lower level of serum testosterone among the infertile men in comparison to the control subjects. When gonadotropins interact with specific receptors on the reproductive cell surface they stimulate gonadal steroidogenesis and gametogenesis, but increased toxic metal concentrations in the tissue have been observed to interact with these receptors on the surface of the cell membrane thereby preventing the gonadotropins from binding to receptors[28] or cause an increase in the production of reactive oxygen species that affect membrane integrity.[41]. This interaction impairs gonadotropic binding, steroidogenesis, and gamete growth.

The observed significantly lower Zn levels in azoospermic and oligozoospermic than normozoospermic men and control subjects, and Zn-positive correlation with serum testosterone level is consistent with previous studies elsewhere.[41,42,43,44]. Zinc activates secretion and action of testosterone and can lead to increased efficiency of spermatogenic machinery and an increased number of germ cells in the seminiferous tubules.[27,42]. Zinc provides a protective role against Cd accumulation, made possible by competition between them at different stages of absorption, distribution, excretion, and the sites of biological actions. Exposure to Cd can lead to the disturbance of Zn concentration while Zn deficiency can lead to Cd accumulation.[45]. Several factors have been associated with low levels of Zn in seminal plasma. Inflammation has been observed to impact the secretory function of the prostate[46] and the accumulation of toxic metals in the testicular tissues may reduce Zn levels in semen.[47,48]. A low Zn/Cd ratio was reported to decrease the immune response of the semen or/and testis.[46]. Other factors that could reduce the seminal plasma Zn concentration are prostatitis, and frequent ejaculation.[49]. The level of Zn is naturally high in the testis and it helps to prevent tissue injury by stressors such as Cd, fluoride, and heat.[3]. Zinc also plays a role in the adjustment of the spermatogonial proliferation and the meiosis of germ cells during early spermatogenesis.[50]. A low Zn concentration disturbs the fatty acid composition of the testis and impairs normal endocrine control of the testis.[51]. The catabolism of lipid present in the sperm-middle piece that provides energy for the motion to spermatozoa is impaired at low-Zn concentration.[3]. It should be stated that Cd has a similar chemical composition and valency to several essential elements such as Zn, iron, and calcium therefore can be absorbed by cells via ionic and “molecular mimicry”[3,52]. Besides, Cd and Zn bind to the same proteins (albumin and metallothionein) in the body and compete for uptake into the cells.[13].

Earlier investigators had noted that zinc deficiency lowers plasma testosterone levels and that Zn is needed for the normal functioning of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis. A clinical study indicated that adult males who were Zn deficient showed a disorder of testosterone synthesis in the Leydig cell since zinc plays a major role in the 5α reductase enzyme that is necessary for the transformation of testosterone into a biologically active form, 5α dihydro-testosterone.[53]. Zinc affects oxygen consumption of the spermatozoa in seminal plasma and also influences head-tail attachment or detachment and nuclear chromatin condensation/ decondensation.[53]. Testicular zinc is crucial for normal spermatogenesis and sperm physiology; it maintains genomic integrity in the sperm and fixes attachment of sperm head to tail.[54].

The observed effect of low Zn levels on sperm indices aligns with previous studies[55,56] and was reported to be due to low Zn in diet. An association of low zinc concentration with poor sperm parameters has been previously reported.[57]. Conversely, several authors have also reported no significant association between Zn levels and semen quality.[58,59]. No association between age of participants and Pb, Cd, and Zn among males evaluated for infertility.

Treatment options for toxic metal toxicity in infertile males are evolving. There is currently no consensus regarding the treatment of toxic metal toxicity since not many human studies have been done. However, clinical protocols are available for the use of Ethylenediaminetetracetic acid (EDTA), 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS), and Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) chelators, which had proved to be therapeutically beneficial.[28]. Adequate evaluation, informed risk modeling to preventing exposure to toxic metals may help to mitigate their health consequences[12].

CONCLUSION

Seminal plasma Pd and Cd may represent reproductive toxicants in non-occupationally exposed infertile males, lower levels of seminal plasma Zn and serum testosterone may also be implicated in male infertility since adequate Zn concentration in seminal plasma and serum testosterone levels are needed for male reproductive health. Seminal plasma levels of Pb, Cd, and Zn may be included in the routine evaluation of the infertile male subjects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contributions of staff of the Department of Medical Microbiology, Human Reproduction, and Research program unit University of Benin Teaching Hospital and staff of the Medical Laboratory service Department of Central Hospital, and the Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Benin City to make this study a success.

REFERENCES

- Alteration of neutral-alpha glucosidase in seminal plasma and correlation with sperm motility among men investigated for infertility Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Fertil Sci Res. 2020;7:111-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation between lead and cadmium concentration and semen quality. Andrologia. 2015;47:887-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zinc is an essential element for male fertility: a review of zn roles in men’s health, germination, sperm quality, and fertilization. J Reprod Infertil. 2018;19:69-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of human zinc deficiency: its impact on human health and disease. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:176-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of dietary zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth performance and antioxidative status in broilers. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;160:361-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of zinc concentrations in blood and seminal plasma and the various sperm parameters between fertile and infertile men. J Androl. 2000;21:53-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are zinc levels in seminal plasma associated with seminal leukocytes and other determinants of semen quality? Fertil Steril. 2002;77:260-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group (IZiNCG) Technical Document #1. Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food and Nutr Bull. 2004;25(Suppl 2):S94-S203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of seminal plasma zinc and serum zinc levels on semen parameters of fertile and infertile males. J Bangladesh Coll Phys Surg. 2017;35:15-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of zinc fractions in human blood and seminal plasma by ultrafiltration and atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;51:267-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of calcium, magnesium, zinc, and copper in blood and seminal plasma on semen parameters in men. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:131-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cadmium mitigation strategies to reduce dietary exposure. J Food Sci. 2020;85:260-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interactions between CADMIUM AND ZINC IN THE ORGANISM. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:967-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of mine-water on agricultural soil quality in Ishiagu, Ebonyi State. Niger J Microbiol. 2009;23:1823-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heavy metal levels in paddy soils and rice (Oryza sativa (L) exposed to agrochemicals at Ikwo, South-East Nigeria. Int J Agric Innovat Res. 2013;2:417-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public health significance of metals’ concentration in soil, water and staple foods in Abakaliki, South-eastern Nigeria. Trends Applied Sci Res. 2007;2:439-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioaccumulation of heavy metals on soil and arable crops grown in abandoned peacock paint industry in Ikot Ekan, Etinam Local Government Area, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Universal J Environ Res Tech. 2014;4:39-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of seminal plasma cadmium levels with semen quality in non-occupationally exposed infertile Nigerian males. J Environ Occupat Sci. 2015;4:40-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sample size determination in health studies; a practical manual. IRIS, World Health Organization; 1991.

- Aetiology, clinical features and treatment outcome of Intrauterine adhesion in Ilorin, Central Nigeria. West Afric J Med. 2008;26:298-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen (5th). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Male infertility in Nigeria: A neglected reproductive health issue requiring attention. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci. 2015;4:45-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gaps in male infertility health services research. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7(suppl 3):S303-S309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cadmium toxicity: a possible cause of male infertility in Nigeria. Reprod Biol. 2006;6:17-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seminal Plasma Levels of Lead and Mercury in Infertile Males in Benin City, Nigeria. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016;5:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reproductive toxicity of metals in men. Arhiv za Higijenu Rada Toksikologiju. 2012;63:35-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cadmium concentrations in blood and seminal plasma: correlations with sperm number and motility in three male populations (infertility patients, artificial insemination donors, and unselected volunteers) Mole Med. 2009;15:248-262.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endocrine disrupting chemicals: Multiple effects on testicular signaling and spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1:231-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of effect of selected trace elements on dynamics of sperm DNA Fragmentation. Postepy Hig Med Dosw(Online). 2015;69:1405-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exposure to As, Cd and Pb-mixture induces Aβ, amyloidogenic APP processing and cognitive impairments via oxidative stress-dependent neuroinflammation in young rats. Toxicol Sci. 2015;143:64-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:92-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the level of trace element zinc in seminal plasma of males and evaluation of its role in male infertility. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2011;1:93-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rising environmental cadmium levels in developing countries: threat to genome stability and health. Environ Anal Toxicol. 2012;2:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma cadmium and zinc and their interrelationship in adult Nigerians:potential health implications. Inter Discip Toxicol. 2015;8:77-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological profile forcadmium. Atlanta, GA: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2012.

- Association of blood and seminal plasma cadmium and lead levels with semen quality in non-occupationally exposed infertile men in Abakaliki, South East Nigeria. J Fam Reprod Health. 2017;11:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse effects of cadmium exposure on mouse sperm. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:550-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of heme oxygenase activity in Leydig and Sertoli cells of the rat testes. Differential distribution of activity and response to cadmium. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:1493-1502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term, low-dose lead exposure alters the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system in the male rat. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:871-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo study on lead, cadmium and zinc supplementations on spermatogenesis in Albino Rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;6:141-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the level of trace element zinc in seminal plasma of males and evaluation of its role in male infertility. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2011;1:93-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elevated dietary intake of Zn-methionate is associated with increased sperm DNA fragmentation in the boar. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:570-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does folic acid and zinc sulphate intervention affect endocrine parameters and sperm characteristics in men. Int J Androl. 2006;29:339-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are zinc levels in seminal plasma associated with seminal leucocytes and other determinants of semen quality? Fertil Steril. 2002;77:260-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of lead and zinc on rat male reproduction at biochemical and histopathological levels. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:507-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cadmium, lead and other metals in relation to semen quality:Human evidence for molybdenum as a male reproductive toxicant. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1473-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between seminal plasma Zinc and semen quality in a subfertile population. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2010;3:124-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zinc-regulating proteins, ZnT-1, and metallothionein I/II are present in different cell populations in the mouse testis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:905-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between abnormal sperm morphology induced by dietary zinc deficiency and lipid composition in testes of growing rats. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:226-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transport pathways for cadmium in the intestine and kidney proximal tubule: Focus on the interaction with essential metals. Toxicol Lett. 2010;198:13-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of zinc concentrations in blood and seminal plasma with various semen parameters in infertile subjects. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:111-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zinc and male reproduction in domestic animals: A review. Indian J Animal Nutr. 2013;30:339-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are zinc levels in seminal plasma associated with seminal leukocytes and other determinants of semen quality? Fertil Steril. 2002;77:260-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between seminal plasma zinc concentration and spermatozoa-zona pellucida binding and the ZP-induced acrosome reaction in subfertile men. Asian J Androl. 2009;11:499-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seminal plasma zinc concentration and alphaglucosidase activity with respect to semen quality. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;110:97-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zinc levels in seminal plasma are associated with sperm quality in fertile and infertile men. Nutr Res. 2009;29:82-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seminal plasma zinc levels and sperm motion characteristics in infertile samples. Chang Gung Med J. 2000;23:260-66.

- [Google Scholar]