Translate this page into:

Successful pregnancy and its outcome in a woman with 46XX gonadal dysgenesis

Address for correspondence: Dr. Papa Dasari, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, JIPMER, Puducherry, India. E-mail: dasaripapa@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A 25-year-old lady with 3 years of primary infertility was diagnosed with an infantile uterus, premature ovarian failure due to streak gonads, and 46XX gonadal dysgenesis. She has received hormone therapy irregularly since menarche and gets withdrawal bleeding only after taking estrogen and progesterone combination. She also received three cycles of ovulation induction elsewhere. Her transvaginal ultrasonogram (USG) showed uterus that measured 4.1 × 2.3 cms, right ovary measured 1.4 × 0.9 × 1.08 cm and left ovary could not be visualized. She was given hormone replacement therapy to achieve optimal uterine size for a period of 1 year and achieved pregnancy with the second cycle of the donor oocyte program. She developed early onset-gestational hypertension and underwent elective lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) at 37 weeks. At cesarean section, fallopian tubes were normal and ovaries were small in size and streak like. An alive female baby was delivered who weighed 3.5 kg.

Keywords

Donor oocyte

gonadal dysgenesis

POF

pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Gonadal dysgenesis is a very rare disorder that occurs during the in utero developmental stage of an individual at the time of fertilization, embryo, or fetus. It is due to errors in cell division and alterations in genetic material and results in a spectrum of disorders causing abnormalities in phenotype or genotype depending on a partial or complete loss of gonadal tissue. The genetics of gonadal dysgenesis include the complete absence of one of the chromosomes 46 XO or its mosaics (Turners Syndrome) 46XX and 46XY (Sweyers Syndrome). Complete gonadal dysgenesis genotypes are 46XX and 46XY and they have streak gonads, primary or secondary amenorrhea, infertility, and absence of features of Turner syndrome.[1] The 46XX type gonadal dysgenesis has a large spectrum ranging from streak ovaries to normal size and may not respond for Gonadotropin stimulation, and is frequently diagnosed as a premature ovarian failure. A young infertile woman who was diagnosed as a premature ovarian failure with hormonal and ultrasonogram (USG) diagnosis of streak gonads with infantile uterus showed 46XX genotype was treated for infertility and the pregnancy outcome is described in this report.

CASE

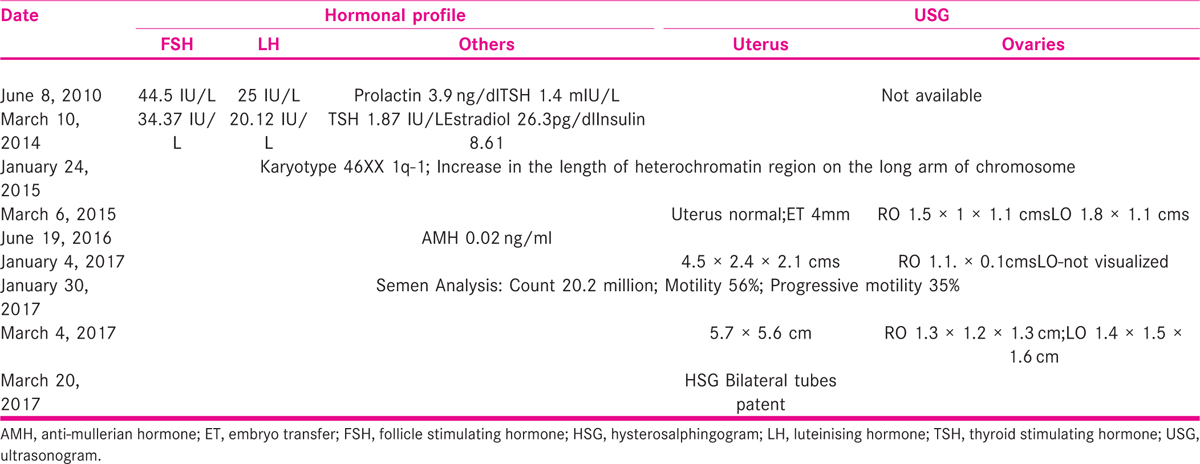

A 25-year-old lady married for 3 years presented in 2017 seeking treatment for infertility. She attained menarche at 15 years of age, cycles were irregular since then with scanty flow. She was investigated elsewhere and found to have raised follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) and was treated with tablet Ovral −G (Ovaral G; Pfzer Ltd; India) for nine cycles and on medroxy progesterone acetate (Deviry 10 mg; Elder Pharmaceuticals; India) on and off. She also received three cycles of ovulation induction with oral ovulogens (Leterozole, two cycles, and Clomiphene Citrate one cycle). She had done investigations at various places that are shown in Table 1.

On examination, she was well built with height of 163 cm; weight 82 kg, and BMI was 30.86 kg/m2. Breasts and thyroid were normal and the respiratory System and cardiovascular system were also normal. Abdominal examination revealed obesity and there was no mass. Gynecological examination showed normal external genitalia. Cervix and vagina were healthy. The uterus was mid position and size could not be made out due to obesity. She had no coital problems. Trans-vaginal scan at our center revealed cochleate shape of the uterus that measured 4.1 × 2.3 cm, right ovary measured 1.4 × 0.9 × 1.08 cm, and left ovary could not be visualized. She was diagnosed with premature ovarian failure (POF) has her FSH was 45 IU/L and LH was 25 IU/L, infantile uterus with streak gonads (46XX gonadal dysgenesis), and counseled regarding the prognosis, necessity of donor oocyte program, and optimizing the size of the uterus before the program. She was advised to take tab Estradiol Valerate 2.5 mg (Progynova; Zydus Cadila Ltd; Tamil Nadu; India) once daily for 30 days and Tab. medroxy progesterone acetate 5 mg (Deviry 10 mg; Elder Pharmaceuticals; India) from Day 14 to 25 for six cycles. She was counseled for adoption and donor egg program, and asked to arrange an egg donor. She returned after 6 months of taking cyclical hormonal therapy. Her uterus measurements are shown in Table 2.

As the donor was not ready, she was asked to continue hormonal treatment for another 6 months.

The donor was 32 years old, had two children, and was tubectomized. She was counseled regarding ovarian hyperstimulation and antagonist protocol was initiated after the basic and hormonal investigations that were normal. She (the donor) developed eight follicles on the right ovary and five follicles on the left sid, e and E2 was 3125 pg/ml. Only five oocytes were obtained and the rest were empty follicles. ICSI was performed and on day 3 and there were only two fertilized eggs: one 1 × 4 cells grade 2 and the other was very poor quality 1 × 2 cell-arrested embryo. These were frozen after counseling regarding the poor chances of pregnancy. The endometrium of the recipient was prepared by hormone replacement therapy (HRT) cycle and she had an embryo transfer (ET) of 11 mm and AB Grade 3 on Doppler on day 24 and ET was performed after thawing. She was continued on estrogen and progesterone support for 2 weeks and did not achieve pregnancy.

She got enrolled in the Donor Oocyte program elsewhere and underwent ET on October 24, 2019, and achieved pregnancy and came for antenatal care to us. She gained 11 kg weight (99 kg). Her luteal support with tab. Dydrogesterone was stopped at 24 weeks and she was on inj.17 α hydroxy-caproate weekly. She developed early on-set gestational hypertension at 22 weeks and was controlled on tab. Labetalol 100 mg twice daily. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was 3.9 mIU/L and was started on 25 μg of Thyroxin. She was also given prophylaxis with Enoxaparin because of Obesity. She underwent Elective lower segment caesarean section (LSCS) at 36 completed weeks at the maternal request and an alive female baby weighed 3.5 kg was born. At LSCS the ovaries were confirmed to be streak (Fig 1). She was discharged on the third postoperative day along with the baby.

- Posterior surface of the uterus after delivery of the fetus and bilateral normal fallopian tubes and streak ovaries

DISCUSSION

Premature ovarian failure affects 1% of young women and is diagnosed when women present with amenorrhea and elevated gonadotropin levels before 40 years of age. It is rare before 20 years and occurs 1 in 1000. The known causes include viral and bacterial infections such as varicella and tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, and iatrogenic factors such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Genetic causes are X chromosome abnormalities, X chromosome deletions, Mosaic karyotype, bone morhogenetic protein (BMP) 15 gene mutations, and autosomal disorders such as galactosemia, gene defect, gonadotropin receptor gene dysfunction, Inhibin gene mutation, and so forth.[2] Environmental factors such as toxins are also cited. Autoimmune thyroiditis and adrenal insufficiency are the other causes that need to be explored and these were negative in this lady.

The genetics of premature ovarian failure include autosomal defects and defects on X chromosomes. It has been known since a long time that the defect on the short arm of the X chromosome (Xp) leads to short stature and somatic abnormalities and deletions in the long arm (Xq) leads to ovarian failure without somatic abnormalities.[3] Deletions of the X chromosome that most commonly occur are X q13. 3- q22, Xq26-q28, and Xp11. 2. Deletions at X q13 region produce primary amenorrhea and at Xp11.2 result in primary or secondary amenorrhea.[4] In this lady, deletion was present. Autosomal translocations can occur in the regions between X q13 and Xq27. Women who were FMR 1 gene mutation carriers can also present as POF. They have a family history of intellectual disability and women with fragile X syndrome can have mental retardation and developmental delay and no such history was present in this lady. FSH and LH receptor gene mutations are also associated with hyper gonadotropic ovarian failure and gene 2p21 is defective in these women. They have a streak or hypoplastic ovaries with primordial or primary follicular dysfunction. The molecular defect is that of Guanine neucleotide regulatory protein (G protein) of Adenylate cyclase and pseudo hypopituitarism or hypothyroidism may be clinically present along with POF.[5] Autoimmune disorders are also associated with genetic disorders and these include Addison’s disease and autoimmune ovarian oophoritis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and so forth. Ovarian biopsy is advised in some cases when ovarian autoimmunity is suspected to be the cause of POF. Approximately 4% to 30% of women with POF may have autoimmune etiology.[6] There was an opportunity to perform an ovarian biopsy on this lady at cesarean section but we did not performed due to COVID times and non-availability of services for histopathology.

Pregnancy can occur spontaneously in idiopathic ovarian failure and also sometimes in Turner mosaics. Spontaneous pregnancy in a woman with stress-induced POF who was on hormone replacement therapy was reported by Firoozeh Akbari Asbagh and colleagues.[7] Another case of POF who conceived while being on HRT recently is on record. Her FSH and LH were 102.2 and 45.9 mIU/L, respectively, and anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) was 0.01 ng/ml and karyotype was normal.[8] Young women with an identifiable genetic and autoimmune cause are to be reassured that they may conceive spontaneously as another case of POF after 10 years of amenorrhea was reported by Ying Gu and Yan XU.[9] The treatment options for POF include HRT, DHEAS, ICSI with donor oocyte, orthotopic ovarian tissue transplantation, and stem cell therapy. A recent systematic review (2008–2018) on pregnancy following a diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency found that the women who achieved pregnancy were very young, the mean age being 30 years. A pregnancy rate of 2.2% to 14.2% was reported employing the latest techniques of umbilical cord blood cell or mesenchymal cell therapy. The RCTs included were underpowered to reach any conclusion and the causes of POF were diverse and idiopathic or autoimmune POF was found to respond to Gonadotropins with corticosteroids with 30% ovulatory rate and pretreatment with estrogens to bring down the level of FSH was advocated.[10] To investigate the resumption of ovarian activity and spontaneous pregnancies in POF, a mixed retrospective, prospective study was undertaken in a referral reproductive endocrinology center that included 358 consecutive POF patients. Ovarian function was resumed in 24% and 4.4% achieved pregnancy in idiopathic POF. The predictive factors for ovarian function resumption were family history of POF, secondary amenorrhea, presence of follicle in the ovary by USG, and estradiol and inhibin levels. Association with autoimmune disorders, presence of follicles at biopsy, anti-mullerian hormone level, and genetic abnormalities did not appear to be predictive. FSH level of between 30 and 50 IU/L at diagnosis was a better prognostic factor than higher levels. In this study, idiopathic POF was diagnosed when there was a history of at least 4 months of amenorrhea, two FSH readings above 30 mIU/ml measured 1 month apart, and a karyotype excluding Turner’s syndrome and gonadal dysgenesis without any history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy.[11] ACOG committee opinion on primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young adults recommends FSH and estradiol levels to be performed twice at least 1 month apart to diagnose POF and states that the evaluation to be undertaken annually.[12]

In the current lady, hormonal evaluation was undertaken more than twice and karyotype showed deletion. A successful pregnancy with donor oocyte program was reported in a woman with Sweyers syndrome who received HRT after gonadectomy.[13] In pure gonadal dysgenesis also, IVF and ET involving donor program are the first line of choice after optimizing the uterine growth and dimensions close to that of normal. They have also observed streak gonads at Caesarean section.[14] Mode of delivery is to be individualized, however, in the literature, it is reported that uterine dysfunction because of the hypoplastic uterus was anticipated and elective cesarean section resulted in better outcomes.[14,15] Finally occurrence of spontaneous pregnancy in pure gonadal dysgenesis 46XX was reported in 2010 and the baby was delivered by cesarean section.[16]

CONCLUSION

Women with POF are to be evaluated carefully and psychological counseling is important to decrease anxiety and achieving pregnancy. The chances of pregnancy depend on the cause as it is a complex disorder. Pregnancy can be achieved in women with pure gonadal dysgenesis with donor oocyte program once uterus is optimally prepared.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Complete gonadal dysgenesis in clinical practice: the 46, XY karyotype accounts for more than one third of cases. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1431-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis and causes of premature ovarian failure: an update. Int J Fertil Steril. 2011;5:54-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familial premature ovarian failure due to an interstitial deletion of the long arm of the X chromosome. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:125-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea associated with a novel mutation of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; clinical, histological, molecular studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3491-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of idiophatic premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:337-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case report of spontaneous pregnancy during hormonal replacement therapy for premature ovarian failure. Iran J Reprod Med. 2011;9:47-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spontaneous pregnancy in a patient with premature ovarian insufficiency − case report. Prz Menopauzalny. 2018;17:139-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful spontaneous pregnancy and live birth in a woman with premature ovarian insufficiency and 10 years of amenorrhea. Front Med. 2020;7:18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy following diagnosis of premature Ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39:467-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Resumption of ovarian function and pregnancies in 358 patients with premature ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3864-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Committee opinion no. 605: primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:193-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rare successful pregnancy in a patient with Swyer Syndrome. Case Rep Womens Health. 2016;12:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in a patient with gonadal dysgenesis. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;36:140-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful triplet pregnancy in an African with pure gonadal dysgenesis: a plus for assisted reproduction. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2015;4:166-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pure gonadal dysgenesis and spontaneous pregnancy: a case report. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:103-4.

- [Google Scholar]